This is the second part of Didier Gazagnadou’s interview for the EURASIA program. (See Part 1 and Part2 here)

In this last part, Didier describes the meaning of anthropological research, mentioning Foucault’s idea of subjectivation and Lévi-Strauss’ paradox on cultural mixture.

This interview was conducted on two occasions (18th January & 5th July 2021) on Zoom. The author edited the two interviews to produce the following text.

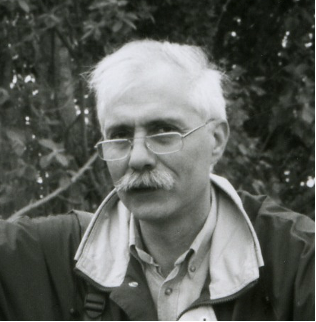

Didier Gazagnadou is a French anthropologist, born in 1952. He is a Full Professor of anthropology (Dr. HDR.) and teaches at the Department of Sociology and Anthropology at University Paris 8 – Vincennes, where he continues his research on technical and cultural diffusion in Eurasia, specially in Iran and the Arab World, with a partially diffusionist approach.

After completing studies in philosophy at the universities of Paris I Pantheon-Sorbonne and Paris VIII – Vincennes à Saint-Denis, Didier Gazagnadou went on to study anthropology. He is now a University Professor in anthropology at University Paris VIII and lead researcher in the laboratory Centre d’Histoire des Sociétés Médiévales et Modernes (MéMo) of Paris 8 and Paris Nanterre Universities. During the course of his career, he was based in Iran on two occasions. First of all in 1993 and then in 1997 (in Teheran), where he was a researcher at the Institut Français de Recherche en Iran (IFRI). He was subsequently posted in the Arabian Peninsula from September 2007 to August 2010, where he worked for the Ministry of Foreign Affairs as Cultural Advisor at the French Embassy in the United Arab Emirates. He is a member of the French Association of Ethnology and Anthropology (A.F.E.A. Association Française d’Ethnologie et d’Anthropologie) and of the “Société Asiatique”.

Dominique

The question of cultural singularity is a very important point to understand when we talk about cultural diffusion. And that also applies to artistic diffusion.

Didier

You are very interested in artists, so on the silk roads. So as far as the Postal relay is concerned, I’ll answer you right away. The posts, the ancient posts on which I worked in my book, for Asia, for the Chinese world, for the Iranian world and even in the more ancient past in Roman times, basically for the posts of Antiquity and the Middle Ages, we can say that they are essentially posts reserved for power.

For a very simple reason, it is that the power is the one that, as I have explained, is able to organize such an institutional machine that requires personnel, animals, etc. Relays. And then, there is the wish of any power, to try to diffuse and recover information discreetly, if not secretly, and at the same to spread it as far as possible, of course, in the empire, in the space held by this same power, but in an almost confidential way in order to have the fastest possible political and military responses.

Dominique

And diplomatic as well.

Didier

And diplomatic. This will change with the invention, it will change at some point in Europe. And there is also a cultural and political history at stake. The Postal relay is going to serve the public, the State is going to propose to individuals to register in order to simplify the process.

But there the important element that we must never forget either, it is that the populations are illiterate, in all the societies until the 19th century, they are mostly illiterate. We cannot imagine that, we who are cultures of communication, we all know how to read and to write. Of course there are still illiterate people, but they are the minority. We can’t imagine what was a society, until the end of the 19th century in Europe, and even later in the remote countryside where people needed a public writer.

Dominique

So it was really only about three percent of the population that could write and read?

Didier

Absolutely.

Dominique

The nobles, the bourgeois and those who belonged to the Church.

Didier

Yes, and the political and artistic elites, and the merchants, the bankers knew how to read and write for good reason. But the majority of the population could not read nor write. And the Postal relay was an operation of State, a machinery of State, which could be only confidential. So obviously we see it developed in China, and inspectors were appointed to supervise the postal relay in China in particular, and in the Mongolian period as well. But the history of illiteracy is absolutely fundamental, and of which all the parts of the culture that we can take. Imagine in the field of religion, and what I see happening in Islam is also striking. Why? Because people don’t know how to read the Quran, they don’t know what’s in the Quran, they know the first sura in general.

But when you go into it, it’s an old, difficult Arabic, with some words that have changed in meaning from modern Arabic and dialects. So people don’t know what’s in the Quran. But we tell them that, there are some nice things and some not so nice things, like in all the texts, but it’s very important. And what is changing in Muslim countries is that there is literacy and people are going to see the texts themselves.

It changes things a lot. Which eventually challenges their parents or their religious in their interpretation of the texts. Because they went to school, because they went to high school, because they went to university. So it’s hard to answer your question about the impact of the diffusions in peaceful terms. I would say that yes and no, it depends on the techniques or the things that are diffused, but in the field of the arts for example, yes, as well as today, I believe that artists must be put in a particular position in the diffusions. They are always a bit ahead of the game.

Dominique

Exactly, they are ahead of schedule, maybe because of their freedom of mind.

Didier

They are always ahead, that is to say, to say to an artist that this music is superior or inferior, it is not an interesting question. What interests an artist is what is going to happen with what she feels, what is going to build as a new musical arrangement, with this or that instrument, with this or that person, this or that group, whatever its origin. Or she will be directly interested as, for example, a European or French artist, in Chinese culture or Japanese culture and will say: Ah, this posture, if it is a Kabuki dancer, is original, I can perhaps do something new with that, and vice versa.

And that’s the strength of artists, artists, musicians. Because I hear musicians, painters, poets, sculptors, really what we call the fields of arts. One also finds on the Silk Roads, if you listened to certain musics of Central Asia, a mixture. I have here the CDs that I brought back from the west of Iran, and more than in the region of Samarkand, that is to say in this region, the old Sogdiana in Bukhara and Samarkand. You have music, it was a very clear mixture of Persian instruments, Chinese vocalism, Turkish variation, finally it is very interesting, it is very original.

So to answer you, I would say that yes, the artists on the Silk Roads have certainly circulated arrangements, musical arrangements, pacifist by definition. Were the stirrups a technical or a peaceful technical arrangement?

Dominique

They seem rather military.

Didier

More like military. Then there is the art. So there is a technique obviously well known of Iranian origin, which has spread in China since Middle Age, it is polo.

Dominique

Polo ? The game of polo?

Didier

The game of polo is believed to be of Iranian origin.

Dominique

And not British as one would think today.

Didier

It’s not British. We have very old representations of polo from Iranian / Persian origin. But it’s very widespread in Asia because there are also scenes I think in China.

Dominique

Yes, I recently saw a painting of Qing dynasty that depicts nobles playing some sort of polo.

Dominique

It is a cultural case of cultural diffusion of Iranian origin.

Didier

There are peaceful diffusions and there are technical elements that become part of a military arrangement, others of a scientific or medical arrangement that circulated many plants, for example on the silk road, including plants used for medicinal purposes.

Dominique

And also the plants that we eat, right?

Didier

And of course, there are plants that are eaten, but for purposes, the one that was dried even easier to transport, it is even almost sure that from the Persian world to the Chinese world, and from the Chinese world to the Persian world, and may be elsewhere and the Indian world too obviously. Dried or less dried or wet plants circulated for medical purposes. There are networks of circulation. For the ancient periods, until there was a break in the frontier, by the installation of frontiers to isolate countries, there were caravan routes, roads of trade.

The people who are the best at creating new networks were there in Eurasia in particular, also elsewhere in Africa, in South Asia, it’s the same, they were traders, peddlers, merchants, financiers, they want to do business and therefore create networks.

Dominique

Trader and merchants created vast networks of communication. That’s what is fascinating also by the view point of diffusion, of the very idea of the relay post, that is to say that it is a diffusion of a technique which concerns, which influences or which even determinate the diffusion, how a communication network is developed, right?

Didier

Exactly.

Dominique

May be we could say that it is also about a diffusion of the methodology of diffusion.

Didier

Yes, we can say like that. We can and we understand that this is a state network, but it’s true that there were, with incidences, that is to say that the caravanserais (N.B.: a roadside inn where travelers (caravaners) could rest and recover from the day’s journey) saw the gradual meeting of both the diffusion of information, normally rather secret, and in any case, commercial networks. So you see all of a sudden the State intersects with capital, if I may say so, in a somewhat simplistic but exaggerated image. But yes, we can say it as you say it, the diffusion.

It’s true that I had the same idea myself, it made me think of these Mongolian postal relay networks that go from Central Asia, from Mongolia in the north of China to Iraq, to the Internet of today. Except that the Internet is much more powerful and quite extraordinary and fast.

Dominique

And what is also striking in listening to your description of the history of the postal relays is that it was a network that required time to travel. The Internet shortcuts time, so ideas are exchanged instantly, but the postal relay necessitated certain time processes before ideas and goods were transported. That is an interesting aspect to elaborate, I think. At the same time, the postal relay at its epitome was an amazingly sophisticated system of network; they could travel in less than three or four weeks between Karakorum (in Mongolia) and Maragheh (Summer Capital of Mongols of Iran near Tabriz).

Didier

Actually I had a big dream. I had proposed it to UNESCO, which had hundreds of millions of dollars to set up a multicultural team, Japanese, Chinese, Mongols, Persians, Arabs, Russians, and so on. I had proposed them to retrace in each country the postal communication routes with computer equipment, to mark if it is 18 km, 20 km, or 22 km between each relay, because all the relays depend on the topography, depend on the climate, and depend on the type of horse.

Unfortunately, this idea hasn’t been realized, but now with the means that we have, we would have a beautiful map, an extraordinary mapping.

Dominique

You wanted to trace the postal relay using real horses?

Didier

You really need to know what kind of horse can gallop. So I’m told a horse can gallop for 15, 20 km, but we would have to check afterwards, we would have to see from Tabriz to Ulaanbaatar if in three-four weeks we could do that, taking turns every 20 km. But it’s worth doing in any case, and to have another idea of a seminar, that with the horse and relay of post, we really learn what was the speed in the Middle Ages.

Dominique

With our criterion of today’s information and communication networks, we tend to think that speed is an a priori value that is superior of course to networks that are slow. People don’t want to use a slow Internet. But when I was thinking about your postal relay, your relay station and this informational network that depended on it, I thought maybe this slowness or this very fact that people had to spend some time going through Central Asia, to go from East to West or from West to East influenced, conditioned the outcome of diffusion. And that, in an interesting way, not just negatively. For instance, the very slowness of the network might have helped travelers to meet people who lived on the road and spend some time with them, to co-create a certain cultural mixture. I sometime think, maybe the Internet is too fast.

Didier

Ah yes, it’s true, that’s an interesting question. Going back to the postal relay system, it depends on the period because the Mongols are the ones who have, unlike other postal relay systems for the premodern period, in any case of the Middle Eastern and Asian world, allowed traders or to use some postal communication network within their system. As I have shown, they had two or three systems in place. They had secret posts for the Khan, fast posts, for the military, for politics. And then a more traditional posts less fast, always for the power but less fast. And then they allowed, hence the evidences that we have in relations of travels that I quoted, Guillaume de Rubrouck (*French Franciscan missionary of the 13th c.), another Armenian traveler, and others like Ibn Battûta (Muslim traveler and author of the 14th c.) could use these posts with a badge (paiza) of Mongolian sovereignty giving them authorization. These are names that we know, and of course probably many other merchants like the famous Marco Polo and his family used these post houses.

And indeed, to go in your direction, it is what certainly nourished the imagination for example, the “Book of Wonders” of Marco Polo. It certainly fed the imagination, his astonishing encounters with cultures, people, cultures that were completely different. And as for speed, you are also right to raise the problem of speed, but knowing that finally, until the invention of the railroads, well of a certain type of evolution of the railway, the speed that the human world knew from the high Antiquity until the 19th century, speed is the horse.

Dominique

That’s right.

Didier

If not what goes fast? And maybe weapons, some weapons like the arrow and the crossbow. The crossbow, which is a Chinese invention again, but it didn’t really spread right away. The idea of speed was for the human the first one,. And it is the speed to horse that was a quite particular dimension.

Dominique

And that was for thousands of years.

Didier

Thousands of years it is the horse that will remain the, it is the horse with which one goes the fastest.

Dominique

We still count the power of cars in horsepower.

Didier

You’re right, it’s the horses, yeah, exactly. So we’ve drifted a little bit, but we’re following your questionnaire, and you’re interested in Lévi-Strauss?

Dominique

Yes, because we had talked about it the last time in our interview. I think that was how you concluded.

Didier

A big question, I was talking about it today with a colleague again this morning, it is a very big question. Because it is indeed what Lévi-Strauss says and repeats, and you know that Lévi-Strauss was fascinated by Japan?

Dominique

Yes.

Didier

And that he wrote his last book “L’autre face de la Lune”, which is a collection of conferences in Japan. He is a great lover, admirer of Japan, and of Japanese culture. But he asks a question, obviously, which is a question that diffusioners must ask themselves, because we must say to ourselves that cultures do indeed exist, the interest of anthropology is to show that different cultures exist and that this makes the world. There is an aesthetic dimension if you like in this discovery, that lots of very different cultures exist, that they have languages, music, musicalities, sonorities, gestures, bodies, creations that are completely singular.

When they are too isolated, which is what anthropology shows, they remain a little bit on themselves, and therefore there is a chance of being the object of transformation. This has to be qualified however; Japanese history shows that it has to be qualified, because Japan has changed. But that’s the idea, and that cultures that manage to exchange, whatever the elements, are enriched. It’s like when you meet someone different and they teach you things that you didn’t know before. So in the diffusion there is exchange, and in the exchange there is richness, creativity.

But by observing the immense diffusion that industrial capitalism has caused from the 19th century onwards over the whole world, the whole of the cultures, we see, I believe it is what Lévi-Strauss fears in “Race and History”, but also repeated in the interview “De près et de loin” much later with Didier Eribon, is that we see too many contacts being put in place, there is a kind of paradox, seeing cultures influencing each other too much, which makes them lose their characteristics. And his anxiety as an anthropologist would be that there is a kind of uniformity of cultures.-

Dominique

Did he take concrete examples when talking about these standardizations?

Didier

In “Race and History” I don’t think there would be a concrete example. But I’m less worried than he is because I observe for example what happens in Iran. I’ve traveled quite a bit, well not enough, but I’ve still taken the time to observe contemporary Iranian culture. It’s true that we all drink Coca Cola, at least once in a while. We all go and eat McDonald’s at least once in a while. But that doesn’t mean that next door, or in Japan, we’re going to love a miso soup, very hot in winter, that’s it. And we’ll go to a small bar specialized in miso soup, and in France, we’ll eat a hot onion soup in winter, you know?

Dominique

Yes, I know both are delicious!

Didier

And then, the secret of the arrangements and at the limit it had to disappear. So I’m going to change the register. The condition of women in the world, for example, is changing. And this is due to the diffusion of feminist ideas, which have been crossing European society since at least, let’s say the end of the 18th century, or the 19th century.

This idea has spread everywhere, women want to be the equals of men. I believe that they do not want to be enslaved anymore by this ancestral domination.

Dominique

Talking about Iran and the Arab world, not much advancement happens in the Muslim world today?

Didier

No but with difficulty, because there men and religion resist. Because unfortunately in Islam and in the Quranic text, the man is said to be superior to the woman (Sura Al-Nissa, verse. 34), and the Quran is their sacred text, we can’t change it. So it is very annoying because it is written.

Dominique

The Bible could also be seen as a very paternalistic and androcentric text.

Didier

Yes, but not to that extent. The Quran is experienced by Muslims as being the work of God directly, in which the prophet Mohammed had no intervention. He was only the recorder and distributor, if you will, of the divine word. And so it’s really inscribed that God afterwards, it’s God’s choice to have made, to have given the authority of the man over the woman, it’s written in black and white, it’s indisputable. But having said that, women are moving in the Muslim world too.

And then life makes us move. Unfortunately, religiously it is very hard and it will take more time, but I wanted to say that, and besides, there have been feminist struggles in the whole Muslim world, there are women’s and feminist organizations. All over the world this idea has spread and it is irreversible in my opinion. And I think it’s good that way, this androcentrism just had to die.

I am less worried than Lévi-Strauss for the rest, because art feeds itself. Artists, as we said earlier, are always been in advance, compose of the invention of new creations. Would we really manage to create a standardization of behaviors?

Dominique

Are you optimistic that art could diffuse freely despite of all the political and societal barriers?

Didier

It seems difficult, there is the barrier. Take the languages, the language is something very important. And of course there are words introduced from one culture to another. When I say “parking” in French, voilà, it is a word that is not French. I say bazar, which is a name of Iranian Persian origin, bazar which passed through the Arab world and arrived in French. Well then, the question on the other hand is interesting, the dosage is important because, if you want, we entered in Europe and maybe in the whole world as you know, there are questions of identity which are restarted now, in particular in Europe with regard to the problem of the immigration, with regard to the problem of Islam in particular, and of the relation to the other cultures.

And this too needs to be thought through with nuance. Of course there are racist people. And it is clear that we must fight against them, whatever the country. But you also have to understand that you have to have a kind of hindsight that I hope the anthropologist has, and the intellectual too. Seeing that it is not simple when, for example, you take the question of immigration in Europe, in all cases, it is not necessarily simple to be in a district where, all of a sudden, people of a certain culture change culture, that is to say cultural behaviors and languages around you, hence the fact that we see in certain districts people leaving a district, traditional French people, to put it simply, leaving a district because they no longer feel comfortable.

We must be nuanced, we shouldn’t say it means that this person is mean or racist. But it’s not easy to relate to people, you have to understand that the relationship between cultures is not easy. And so there, the notion of dosage, I think I remember that Lévi-Strauss takes up “De près et de loin” (From near and far), he says that it is necessary to maintain a diversity, that’s for sure. And therefore, to maintain diversity, there must be a dosage of transformation of relations, of the cultures themselves, you see?

If we all think in the same way, it’s a horror. I mean when we see Japan, in Japan it’s true that we see very well that in Japan that there is a will to maintain, for example, all these matsuri (traditional festivities) everywhere. These quite extraordinary celebrations in all the regions for this or that fact, etc.

I can understand that one can want to keep this. I don’t think as an ethnologist, that it is racist. But afterwards, because it’s very beautiful, because it’s original, because it’s the only one who has it, because it’s original, it’s part of Japanese culture. Which would not justify for me at the same time the rejection of the Koreans or the other local ethnicities that have contributed in building that culture. It’s all a question of finesse, of dosage, of complexity at the same time.

And then there was history, as you said, colonizations that also weigh heavily, that make things complex. The European colonizations that led to interesting things. In South Asia, in French Indochina, when you see some of the old archives, the whites were transported, as in Subsaharan Africa, by porters, chairs, etc. So, obviously, colonization is a system of domination.

And it was obviously worse in Central and South America where, as we know from the 16th century, the Spanish and the Portuguese (then others Europeans) exterminated the native populations by disease, by viruses, but also by violence. So I really believe that Lévi-Strauss is a really remarkable man, with nuances. And he was interested in diffusion, and also in the first part of his life, we found an old text of his, between texts of the 1930s on the question of diffusion, well a little abstract but which showed that he was interested in that (Lévi-Strauss, De Montaigne à Montaigne, édition de l’EHESS, Paris, 2016).

Claude Lévi-Strauss

Editions de l’EHESS, 2016

Already in “Race and History” there is one of the references to this question of the relations between cultures.

And there are the works too, he talks about it a little in “Anthropology facing the problems of the contemporary world”. And there are some extremely interesting positions on assisted reproduction, etc. It was very interesting what he said about ancient societies that already had practices of this kind. It was very interesting what he said in relation to ancient societies that already had practices that would be scandalous today, where a woman has another man carry her child, but it is integrated in the African culture. It is very interesting. I find that the anthropological view, which is an obligatory distancing from oneself, from one’s prejudices, is quite fundamental, quite fascinating.

Dominique

Thank you very much. Listening to you now, I think I have understood why I am so interested in this idea of cultural diffusion. Because maybe it’s a way, as you just said, to better understand oneself and the Others as well.

Didier

I really believe so.

Dominique

So maybe it’s not so simple as if we were making a declaration of human rights or of human equality, but maybe it’s a scientific methodology to get to know ourselves better. And that’s why I, as a multiethnic person, can relate to this anthropologic view of cultural diffusion.

My Vietnamese grandmother spoke French, because at her time Indochina was colonized by France. My Taiwanese grandfather was raised as Japanese citizen because Taiwan was colonized by Japan. And my maternal grandparents escaped Manchuria, another Japanese colony, at the end of WW II, and my mother basically lived in post-war Japan which was occupied by the US, and still is to certain extent. So from the point of view of international relations, I’m a complex outcome of multiple colonizations which are bidirectional. This is why I’m interested in cultural or artistic diffusion as a means to understand and accept the negative past and affirm a multicultural future.

Didier

It’s interesting what you say, because you are indeed a mixed race. But it is the opposite for me, because I do not have multiple origins, my father was from Auvergne and my mother from Lorraine, therefore the lineages are more or less clearly established. And therefore it comes to me from elsewhere, how it comes on the other hand the interest of others, the interest to the foreign cultures, it can be also in systems of oppositions of distinction with regard to precisely too many similarities.

So you see, diffusion has effects as we said earlier. It could lead in some cases, even in the case of miscegenation, to a withdrawal, saying to oneself: Oh no, I’m only Vietnamese, for example. Or no, no, don’t talk to me about Vietnam, I’m Japanese, I don’t want to hear anything more. Or in a case like mine it could be: I’m only French, that’s fine.

So the mechanisms also intrapersonal, the personal dynamics of construction, what we call with Foucault now, “mode of subjectivation”. It is the relation of oneself that organizes the relation to the other, to very specific mobilities and constructions, according to very specific individualizations. And it is the same for the cultures besides. The perception of oneself, the perception of the other, the glance of oneself on oneself. Then there is an evolution… Obviously the Deleuzian or Foucauldian philosophy, there is a setting up of new concepts which allow to understand better precisely, a subjectivity.

The idea of subjectivation is a modality which is in movement at the same time, therefore which is the object of agency, of rearrangement, of reterritorialization, of territorialization and of system of perception, at the same time of oneself in a situation and with the other movements or in permanent agency.

Dominique

I understand.

Didier

A recompilation. So, did the technical diffusions play a role? Yes. And especially contemporary ones? and I would answer yes. The diffusion of contemporary communication and information technologies has played a role, for better or worse, absolutely central in the recomposition or composition of new modes of subjectivation. It is absolutely like that, but for better and for worse. Because I don’t know what’s going on in Japanese social networks. But in Europe, we talk about it a lot in France, there is nonsense, violence, ideology, religion and we talk about a lot in relation to Islam.

Dominique

At least I know the structure of hate speech is the same in Japan and the United States.

Quoting Lévi-Strauss perhaps it is a case of being too open to other cultures at the same time, and perhaps even too quickly, that led this general mood of ungenerosity in the social media. So this might be a structural problem of a network system that is too fast.

Didier

Yes, maybe exactly right. Excellent point. Too much speed perhaps subjugates or metabolizes the relation between oneself to others.

Dominique

And this fastness might be generating a general sense of fatigue everywhere when using this technology, even among very young people in Japan or in France.

Didier

It produces the anguish arrangements.

Dominique

Yes, anxiety or complexes, and fears of others. Can I really ask you one last question before I let you go? It’s a short question, about this tribute you wrote for Gilles Deleuze, which is a fantastic text.

And there, you seem to be describing how Gilles Deleuze came to conceive his idea of nomadology. And why he was interested in this idea of tensions between nomads and sedentary states. And among your text, I was very struck by what he said, such as: “Well, maybe the nomads treat their people as cattle, as animals. But so what? Do you think that the States, who treat their people like a tree that are cut every year, are better?”

I’m bringing up this text of you, because our interview today reminded me of Gilles Deleuze’s story, who was interested in nomads, to perhaps think about an alternative mode of perception or construction of an alternative world to the one that is dominant today, that is to say, a state of discipline and surveillance as Foucault well described.

Do you also have this same direction of curiosity towards this idea of cultural diffusion? Do you conceive in your imagination or in your fantasy an alternative world, thinking about the whole history of cultural diffusion like Gilles Deleuze?

Didier

So, if I’m honest with you, I think that there is a really personal dimension. A story linked to my personal childhood history. I think that very early on I met foreigners at elementary school, so who were North Africans. I had North African friends and Arab friends. And I believe that certainly that the opposition of my parents to these relations, because it was in full war of Algeria, perhaps, you see, created me perhaps an arrangement of exit (une ligne de fuite).

Dominique

So you had a fight with your parents?

Didier

Not to argue directly. That’s why I say it’s still a construction, it’s an internal construction. It’s an assumption, that’s why I can’t answer you directly. But things have matured a lot afterwards. But now I’m trying to answer you spontaneously. I think there is a very psychoanalytical or schizo-analytical dimension, if you want to be more Deleuzian. So the Algerian war, the family, foreign Arab people, creates a personal agency and there’s this complexion there. Obviously, in high school we were several nationalities, people of different origins. In particular people from the Maghreb, but also from Asia.

Dominique

Were you in Paris at that time?

Didier

No, in the Paris suburbs. But you see now this suburb where I lived is now completely Maghrebi. And so it’s less interesting.

Dominique

There is less diversity now.

Didier

There is less diversity, the dosage has changed. And there it was quite exciting back then. I believe that I was always interested, I liked to meet foreigners because of this perhaps infantile incident. And that organized in me reflections. I began to travel to the Maghreb.

Dominique

Were you traveling to the Maghreb as a high school student?

Didier

Yes, high school. And then it developed, and then I went around the world. And so I wanted to meet, well I met people for example from Japan, and then I wanted to know Japan, through the individuals.

We also want to build a lot of imagination. And eventually you want to know more. An individual is a multiple landscape, it is affects, it is a world. It is very beautiful. And it is a world of dreams and fantasies too. And so I began to go to Japan, and I returned four times. And then I met other people and I started to go to Iran.

It is really a complex construction, it is difficult to answer your question. But then I see all the anthropological interest in it. I have nothing against those who deal with homogeneous things. Everyone has his own way with the world, I don’t want to judge it at all. But obviously I see the interest. What I missed, what I would not have succeeded in, was to know languages well, I wanted to know many languages. I did Japanese for a year, I did Chinese for a year. I’ve done Arabic and Persian, which is a little better, but it’s still pathetic compared to what I should know. And that’s a bit of a regret that I’ll never be able to overcome until I die. Because it’s much more, if I had known Japanese, I think I would have made an anthropology of Japan, that’s clear, with my own approaches.

Dominique

Thank you very much Didier. I’m very much touched to know your personal journey which led you to the world of anthropology. And I’m especially moved by your expression: “an individual is a multiple landscape and affects”; I somewhat feel empowered when I heard that. I really appreciate your willingness to disclose your private thoughts at the end of this interview. And finally, thank you so much for teaching me all your knowledge and insights on the history of cultural diffusion in Eurasia. I hope to visit you soon in Paris, and I already start dreaming of a day we could visit Central Asia together. So thank you again.

Didier

Thank you very much Dominique. Good luck, good continuation. Goodbye.

Dominique

Goodbye Didier.

Through two interviews, Didier taught me the epistemology of cultural diffusion, which helped me to understand that the history of Central Eurasia is even more complex and fascinating. In addition, the fact that there are still many mysteries that remain unsolved even with the meticulous methodology of cultural anthropology makes me even more curious about not only Central Eurasia, but also the interactions between the East and West of Eurasia. Finally, when he shared with me his personal background that led him to the study of cultural diffusion, his phrase “An individual is a multiple landscape, it is affects, it is a world.” left a deep impression on me. An individual cannot be reduced to a single nation, culture, or region, but rather is a field where diverse worlds are superimposed. That is why there is an inherent limit to classifying people according to their national origin or race for the sake of clarity. I was attracted to Didier’s work because I sensed this philosophy. We could probably get closer to cultures with histories different from our own, by imagining that the world is full of invisible traces of cultural exchange that are left out of the History.

- License:

- CC-BY