In late 2020, as I was exploring the links between Beuys and Eurasia, Kayoko Isogaya, a friend of mine and an art editor, told me about one of her teachers who met Beuys in the 70’s. His name is Shinichro Yoshida, an artist living today in Kyoto. In his youth, Mr. Yoshida used to draw paintings, but after his encounter with Beuys, he started to make serious commitment to the world of fabrics and clothes. I was deeply fascinated by his story, since I was thinking that Beuys’ concept of “expanded notion of art” would eventually lead to think seriously about the nature and meaning of artisanship. Thanks to Kayoko’s introduction, Mr. Yoshida kindly accepted my offer to interview him, and generously told me his story for more than two hours.

In this first section of a twofold article, Mr. Yoshida explains how his concept of working as an artist evolved after he met Beuys in Kassel.

The interview was conducted via Zoom, on 10th of February, 2021.

Shinichiro Yoshida

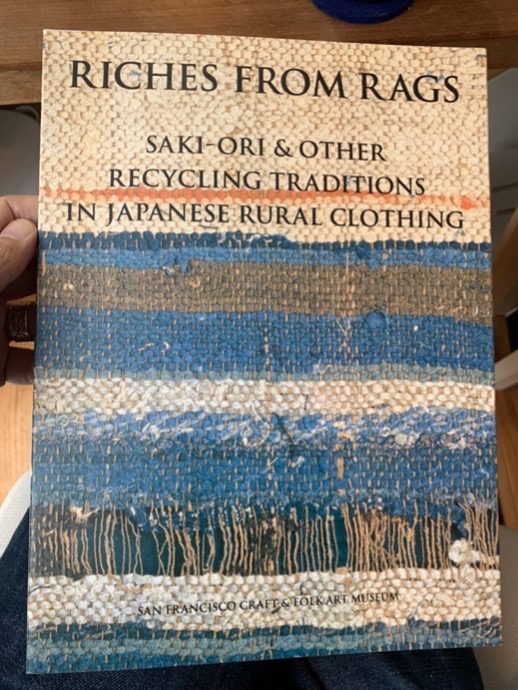

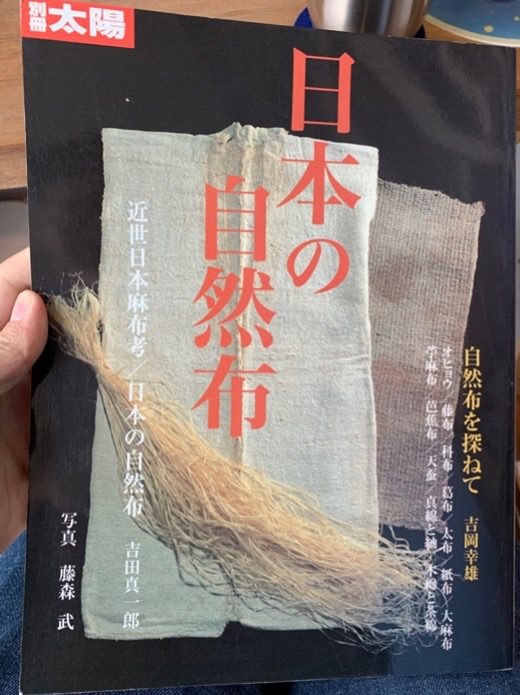

Born in 1948 in Kyoto, Japan. Artist, Director of the Early Modern Asafu (Hemp Cloth) Laboratory. He has organized and participated in various exhibition of his collection of traditional clothes. One of his recent installation is « White » shown at Yamaguchi Center for Arts and Media (YCAM) in 2017. His main publications include the magazine Taiyo Special Edition: Natural Fabrics of Japan”, Heibonsha, 2004, and the exhibition catalogues of “The Cloth that Sustained the Nanto: Nara Sarashi” (2016), “Takamiya Cloth” (2007), “Raw Materials for Nara Sarashi” (2006), “Four Great Linen Cloths” (2012), and “Riches from Rags” (1994). He was awarded the Mizuki Jugodo prize for his outstanding research of Japanese fabrics.

Chen: Hello.

Yoshida: Hello.

Chen: Very nice to meet you. Thank you very much for your time. My name is Dominique Chen.

Yoshida: I’m Yoshida.

Chen: As I mentioned in my email, this year is the 100th anniversary of the birth of Joseph Beuys, and we are looking back at his achievements and thinking about their meaning today. I am in charge of a program that considers the concept of Eurasia, and we are investigating the theme of bridging East and West, starting from Central Asia. The reason I asked for an interview with you today is that I would like to hear about your meeting with Beuys in the 1970s, and how you came to collect and research various Japanese textiles after you left the production of art works. Beuys dealt with nomadic felts from Central Asia, but why did you focus on Japanese fabrics? I would like to hear about that as well.

The artistic director of this project is Mizuki Takahashi, who is currently the curator and director of CHAT in Hong Kong, but I understand that she is also a friend of yours.

Yoshida: She came to see me once for a completely different matter, and then she came to see me for the cloth.

Chen: Oh, I see.

Yoshida: When we were talking, we got to talking about Beuys, and she said she curated an exhibition on Beuys. She asked me if I could come see the show.

But I haven’t talked about Beuys much since I was young. When I came back to Japan, I couldn’t make any more works because of many reasons. I’ve been trying to make new works every day for about 20 years. I didn’t tell anyone about it, but I thought it was enough.

Chen: I see. You met Beuys in 1977 at Dokumenta VI in Kassel, if I’m correct?

Yoshida: Yes, I came back to Japan when I was about 27. So I met him a little before that. Beuys would often ask me questions. But it wasn’t like as a teacher, it was like we were friends. I didn’t know anything about Joseph Beuys back then. I had shown my works, and they were painting on white canvases using only white paint, although I didn’t have big boards. In Japanese galleries and art, they didn’t pay any attention to my works, but in Germany they showed interest.

Chen: Who? Joseph Beuys?

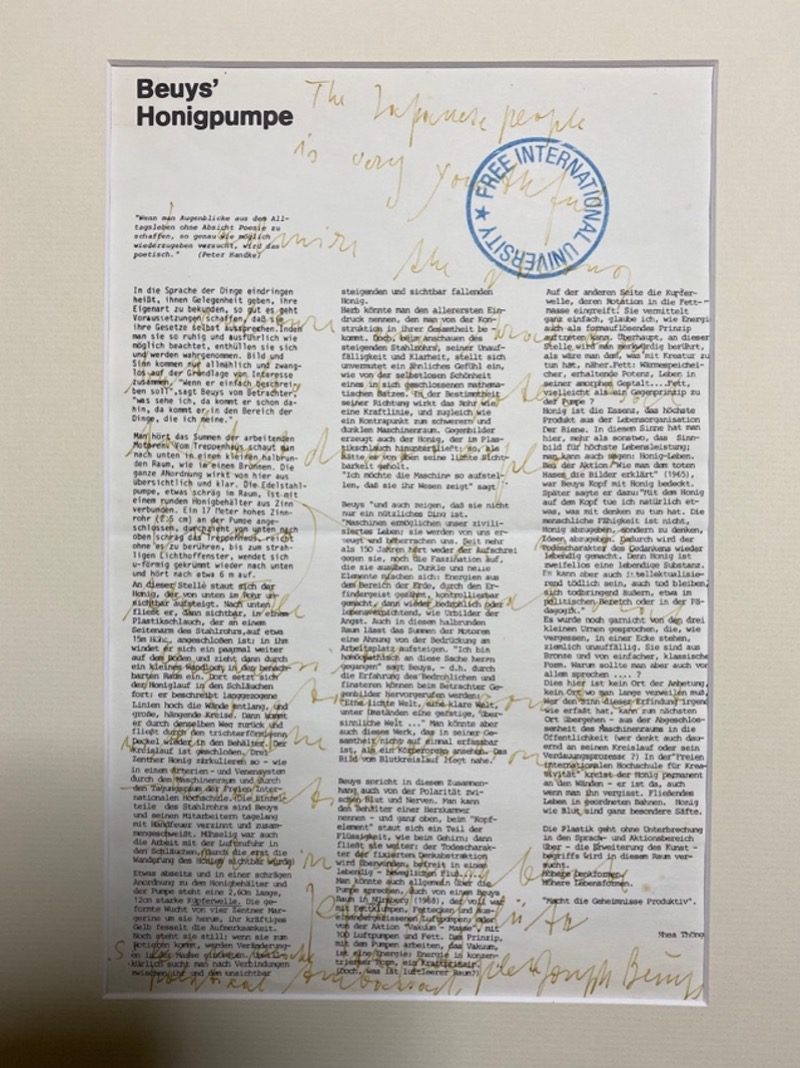

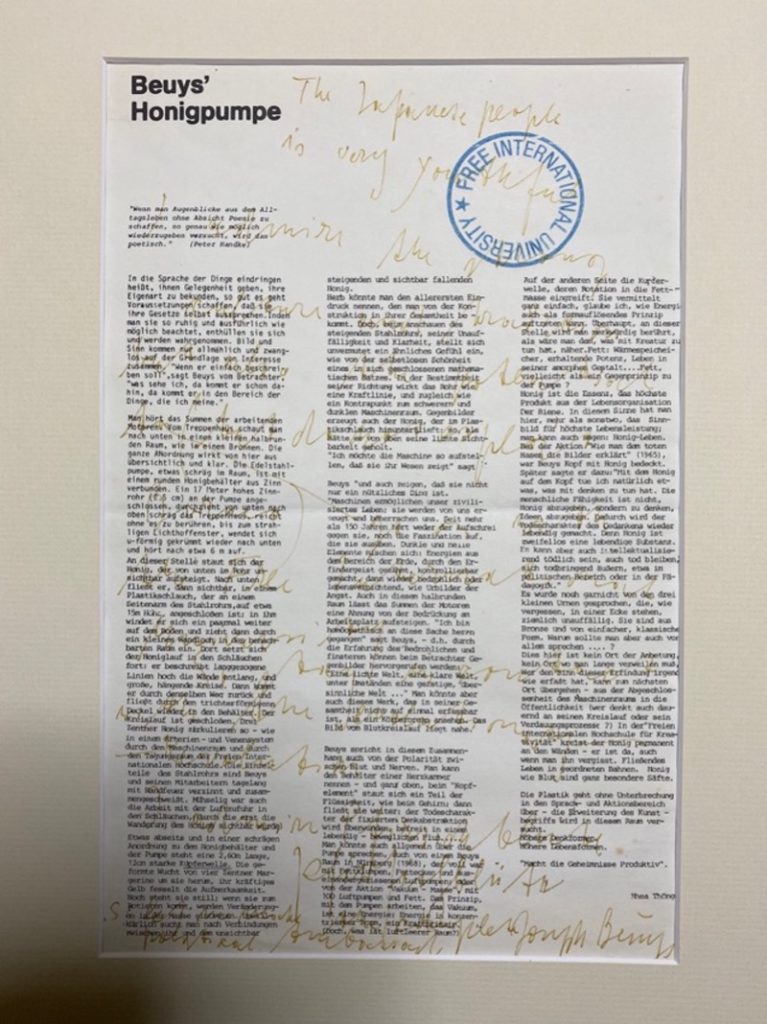

Yoshida: No, his friends. Young guys. They might have been the students of Beuys’ school, the painters. I don’t know. He didn’t say anything at all at the time, but the Kassel Dokumenta were just open at the time, so he took me there. They took me to a big, huge room. I think it was butter and honey, and they were mixing them with a big motor like a concrete mixer. [“Honeypump at the Workplace”] At the time, I didn’t understand it at all. I was like, “Why is this art?” So I kept looking at each room, and I saw pipes, hose-like pipes, going through each place, all the way to the ceiling, and in one room, the pipes were falling down. It’s like a drop. And it was a white piece of paper, maybe a meter square. I don’t know if it was smaller, I don’t remember, but there was a huge pile of them.

Chen: And the drops would just fall down.

Yoshida: That’s right. They would fall. A drop, a drop, a drop. After two, three, or four hours, it becomes a stain of about 40 to 50 centimeters. On the white paper.

Chen: The liquid soaked through the entire pile of paper.

Yoshida: The whole paper was about one meter square, or was it one meter square? I think I might have been a little smaller, though.

Chen: That’s about right.

Yoshida: It’s about a circle. Beuys would sign it.

Chen: I see.

Yoshida: And some gallery or art dealer, I don’t know, would take it.

Chen:: So they just take it?

Yoshida: In the end, they take it piece by piece. They put them in a frame and show them to the store, and they look really cool. From the top. I didn’t know why it was art at that time. I was seriously doing drawings and sketches at that time. In Japan, I was still doing drawing and sketching, day in and day out, all night long, in a daze. Then what I saw was just drops and drops. But I thought it was unusually cool. I was like, “Who the hell is this guy?” Then one of the Beuys guys to whom I showed my painting introduced me to Beuys. There were about twenty of them, and they came out, and Beuys came in the middle, and he said he wanted to ask me questions. So we started talking about roots. He asked me: “Why do you use white? Why do you paint in white?”

Chen: So he was asking you about the concept?

Yoshida: Yes. But I was just trying to paint with my senses. I didn’t know what it meant. Today I understand it better, I know how to answer. But back then, I didn’t think about my history or roots, I just let my senses take over.

Chen: So you intuitively chose white?

Yoshida: It was intuitive. So, it’s not something that can be explained at all. It’s a feeling. That’s why Beuys said it doesn’t make sense to him.

Chen: I see. I’m sure Beuys would have said that to you.

Yoshida: He said it. I don’t know if he said it that way or not. He said it in such a nuanced way. That’s the first time in my life I’ve been asked such a question for my painting.

Chen: Is that so?

Yoshida: It was the first time I looked at my work from such an angle, and I was already puzzled by such a question. First of all, he asked me where I came from, and then he asked me about Japan. He wanted to know about Japan. I thought I could explain about Japan, so I said, “Okay,” and he said, “No, tell me about the relationship between white and Japan.”

Chen: I see.

Yoshida: It was like, “Why are you here?” I didn’t understand the question at all at first. This is a drawing that I, a Japanese person, would draw, and then I was not recognized at all. Galleries don’t take me seriously, and I don’t even want to sell them. I don’t really remember, but that’s how I answered. But Beuys kept asking me questions about it. He wanted to know so much about Japan.

If Beuys had met with people who could answer those questions more properly, he would have been able to know more about the Japanese people. I could have told him more about what he wanted to know now, and I feel sorry for that now. At that time, I really hadn’t thought about it, had I? I never thought about my roots. It was just something that I heard from my parents before my grandparents. So, I went back to the inn and went on with my life, thinking about Japan and the fact that he was a person who said things that I didn’t understand at the time. He said something like, “Hey, come back tomorrow.” The ticket was signed by Beuys, and he gave me a card. It’s like a card that you wear around your neck. With this card, you have a free pass and can come in from anywhere.

Chen: You could visit the Dokumenta any way you wanted.

Yoshida: I started going there every day. Then he would take me to restaurants, and we would eat in the neighborhood, drink tea, and so on. There were always about 10 people around him.

Chen: So there were that many always? His followers.

Yoshida: Yes, there were. I really don’t understand why there were so many of them. Later on, I realized that there were biologists, doctors, economists, old people, young people, there were always about ten of them, both old and young. I remember one with beards who looked like they were old men. Later, I was told that he was a biologist. I couldn’t communicate that well in German or English, so I couldn’t really talk to them.

Chen: So you were speaking in English at that time?

Yoshida: That’s right. All in English. And then there was a German guy who could speak a little Japanese. He said, “Hey, come in.” He had studied abroad in Japan, and he helped me out.

Then, when I wondered about art, biology, economics, and so on, he went to the venue where there were always about 200 people gathered, and suddenly there were about 10 panelists, and the discussion started with a microphone. I couldn’t understand what was being discussed, but anyway, there were about 200 people there. When they asked questions, Beuys would answer them, and when Beuys couldn’t answer, he would pass the microphone to a biologist. It was like the biologist was answering the questions. And now they’re talking about money and things like that.

Chen: An economist.

Yoshida: His colleague did the job. And then, this time, after Beuys answered, he handed over the microphone to a guy who looked like an economist, and that was the discussion with a great deal of bickering.

Chen: Like a debate.

Yoshida: A debate. I think it’s near the venue of Dokumenta, though.

Chen: Did he have discussions every day?

Yoshida: I think he did. I would go out and hang out every day at whatever time I wanted, so it might have been after I was gone. Anyway, I guess there was something going on everyday.

He had a lot of interviews. I got the sense that he was a popular person in Germany, and I was hanging around with him in Kassel. When we were walking to this restaurant together, about ten people would come along with us again. When I was walking with Beuys, four or five girls came up to us in the street and suddenly put a rose on Beuys’s chest. It was out of the blue.

Chen: He was like an idol, wasn’t he?

Yoshida: An idol. Thinking about it now. It was out of the blue. It’s not like they asked for an autograph. They just came up to Beuys.

Chen: They gave him a rose.

Yoshida: I didn’t understand what was going on. I was like, “What is this guy doing here?” I thought he was popular. Then, I went to eat at a restaurant, which was small, like a teishokuya in Japan. It wasn’t a fancy restaurant, but a cheap set meal place like a soba restaurant. Over there, they don’t just wipe it on the desk like in Japan, they have a white cover. They have white covers, cloth covers. There are several desks, and he kept on stamping on them.

Chen: A stamp with his name on it? Joseph Beuys.

Yoshida: Yes. With the cross mark.

He had a few different stamps. From inside his vest. And he would write something on the cloth. I was afraid the owner would get angry. But Beuys didn’t care. When I told him, “You’re doing this without permission,” he just shut up and left. So that’s the way it is in Germany, I thought. After I understood that the person who gave him the roses was a fan of Beuys. But at that time, I didn’t understand it at all.

Chen: That’s interesting. By the way, how many days did you go to the Dokumenta?

Yoshida: Ten days, ten days, two weeks, I think.

Chen: For about two weeks, you were there almost every day.

Yoshida: Every day. I got a ticket. So, I wasn’t just there for the purpose of going to Germany. But when I was drawing all the time in Japan, and I was up all night, then I started to have panic attacks. I felt like I was going to die. There was no name for what is now called panic disorder, so I was afraid I was going to die, so I decided that if I was going to die young, I would rather see art from around the world, from Italy, Germany, France, Europe, and the U.S. with my own eyes, not through magazines.

I thought that I would die early anyway, that I was not going to live much longer. Anyway, I decided to go to Germany first, and then I went there and met Beuys for the first time.

Chen: And you met Beuys first out of the blue?

Yoshida: Yes, it was the first time.

Chen: That’s intense.

Yoshida: Because I met him first, I didn’t just go on to the next one, but day by day I became more and more curious about the meaning of what I was drawing. And the fact that I’m drawn to white, I’m sure there’s something about it that this guy is talking about. My own something. For example, the white that a German paints with the same kind of white paint, and the white that a Japanese painter from Asia paints, may look the same, but they are completely different. After all, it was about the expression. The meaning will be different. That’s what I thought, and I started to wonder about it more and more. I began to wonder why I myself painted white. It wasn’t like I was just going along with the flow, like, “Why not?” At that time, I was really embarrassed, and this is really something that I’m laughing about now, but I know now that I was drawing without meaning and I understand that now. But Beuys would question about every single line I’d draw.

Chen: On the other hand, when you were not taken seriously by galleries in Japan, did you ever have to deal with the kind of questions that Beuys asked you?

Yoshida: First of all, I was not very good at that kind of places.

Chen: You never approached galleries.

Yoshida: Even in the places I knew, there was no reaction when I showed my work to them.

Chen: So there was no response? Not even a question.

Yoshida: Not even a response. So when my trip was over, I thought, “This is no time to be traveling abroad,” so I came back to Japan right away. Rather than looking at other people’s works in foreign countries and worrying about them, I thought to myself, “I can’t do this anymore. It’s not like this. I have to start all over again.” I mean, I’m starting over, and I’m wondering what kind of person I am, rather than what kind of art or painting I’m doing.

Chen: You started to wonder who you were.

Yoshida: That’s how I came back, and then I started traveling around the country. I ended up collecting cloth, and then I started collecting cloth to start painting. I went to Akita, Aomori, and Hiroshima. Anyway, I wondered what kind of old things people wore. I wondered what the Japanese people wore. It was almost ethnographic research, after all. I started with things that had nothing to do with art, like what kind of clothing did the Japanese people wear and what were the materials used to make it. I started with food, clothing, and housing. I suppose anything would have been fine. In my case, I started with cloth, and with a light heart, I thought that I would use it to make my own work. I didn’t think that I would definitely make such a big work, but as I was researching, I thought that if I accumulated a lot of cloth, I would make a work with it and go to Germany to show it to Beuys. So I bought a microscope and started researching what kind of thread these clothes were. The people who gave me the hemp, my parents, and the dealers who handled it all said that it was rough hemp or brownish hemp, no matter where I went, whether I went to Akita or Aomori. They said that everything except cotton and silk is hemp. This is thick hemp, this is thin hemp, and I started collecting them. I collected them because I liked them as materials, but I also played with them, using a microscope to examine the fibers.

Chen: In your book, “Riches from Rags” (San Francisco Craft&Folk Art Museum, 1994) you also include pictures you took with a microscope.

Yoshida: I’ve never said that I’m a cloth researcher but these days, but it’s just a title that museums use to refer to me, and initially I had no intention of studying cloth at all. So I started doing it just for fun, and a couple of people helped me. They helped me with the microscope. Then I found out that there was a fabric in the hemp, called Kudzu cloth. [Kudzu is a type of vine also called Japanese or Chinese arrowroot]

I didn’t understand it at first. I was like, “What is this?” But when I read in books that people used to do business with kudzu cloth in the Edo period, I went to visit the people who said they used to deal kudzu cloth, and listened to their stories. Kudzu-yu (Kudzu hot tea), or kudzu mochi (rice cake with Kudzu) are still sold in candy stores and snack shops.

Chen: We eat it a lot at home too.

Yoshida: Like the cold medicine Kakkonto.

Chen: So kudzu is the root of kudzu plant.

Yoshida: The roots are still used today. But with the kudzu fibers, you have what we call weeds growing on the bank. But in the Edo period, they took the fiber from the weeds and made it into thread, and there are still quite a few of those kimono left from the Edo period. So, I wondered if kudzu was this kind of fiber. In the meantime, Oo-Asa (Cannabis sativa), also called hemp, has been recognized as a narcotic drug since 1945 by the US GHQ [General Headquarters of the American occupying army after the WWII].

Chen: So it has been forbidden by the GHQ.

Yoshida: That’s right. The Torihama shell mound in Fukui Prefecture is a 10,000 year old ruin, and hemp cloth has been found there. It’s only recently. I’m sorry for jumping the gun.

Chen: No, no, no. It’s very interesting.

Yoshida: It’s all a bit related.

However, according to a recent survey, the Torihama shell mound is the most ancient site in the early Jomon period, dating back about 10,000 years, and hemp cloth and string were found there, so I went there five or six times, although I had already done a survey a long time ago. Recently, the National Museum of Ethnology in Sakura City, Chiba Prefecture, announced that ancient Japanese had cultivated hemp around the Torihama shell mound in the early Jomon period. When they announced it, they asked how they knew it was cultivated, and when they examined the soil in the area, they found pollen. They said they were going to keep studying the pollen.

Chen: So it’s concentrated there?

Yoshida: Most people think that hemp grew naturally in the wild, and that the Jomon must have collected it and cultivated it in ancient times. However, it is more likely that they cultivated it under controlled conditions.

Chen: They did it mainly to make clothes.

Yoshida: That’s right. Not only clothes, but also strings, and the various living tools must have been made. So, strings and traces of strings have come out, and then, although at that time it was not weaving but knitting, it must have been knitted clothes, and they must have become clothes. Many fragments of it have been found. Japan has been cultivating hemp for about 10,000. So when you think about it, the Edo period [17th to 19th century] is just recent history.

Chen: A few hundred years ago and 10,000 years ago are completely different.

Yoshida: So, in the Japanese archipelago where hemp cultivation has been going on for such a long time, all of a sudden in 1945, after Japan lost the WWII, the US GHQ said that it was a drug.

They issued a notice to all the farmers in the country. They said that Japanese agriculture would be banned from producing hemp. But the farmers didn’t know why. What do you mean by “narcotics”?

Chen: Because no one was using it for that purpose anymore, right? They weren’t growing hemp to smoke, they were growing it to make cloth.

Yoshida: Yes. It’s a cloth. Nowadays, cotton is generally used in most clothing, but cotton has been used in Japan only since the Edo period. Until then, cotton could not be cultivated in Japan. It spread during the Edo period. I became very interested in what the Japanese people wore when they did not have cotton. I hadn’t planned to study this kind of thing at all, but as I got deeper and deeper into it, I found that I became immersed in the fields that no one else was doing. More and more. The reason why I’m so attracted is that as I learn more and more, more and more things come up that I don’t understand.

Chen: More and more things come up. You don’t get bored at all. That’s what’s so interesting about research.

Yoshida: You never get bored. When I understand something to some extent, I think, “I’ll stop. I’ll stop doing this.” I have to get back to my work as soon as possible, so I don’t think this is the time to be doing this, but the Kudzu clothes keep coming out, and the Fuji [Japanese wisteria] cloth keeps coming out. The Ainu people wore a type of cloth made of a plant called Ohyo [Ulmus laciniata], which is also different from hemp. There are about 15 kinds of fibers. These are the materials worn by Japanese people before the cotton came in. All throughout the Yayoi period, the Nara period, the Heian period, the Kamakura period, and the Muromachi period. These were the common people. The aristocrats and the upper part of the samurai class were 10%, and 90% of the population were the common people. In those days, people did not go to stores and buy things with money as we do today. Everything was done almost entirely on a self-sufficient basis.

Then, such things were barely available when I came back to Japan after meeting Beuys, about 40 years ago, right? At that time, you were still able to collect such things.

Chen: So you can’t find them anymore?

Yoshida: Not anymore. I had a few shows at the Kabuki-za theater and abroad, and while I was doing that, my book “Riches from Rags” became a hit in overseas, and then the price went up a lot.

he same goes for rags. When I was working on Riches from Rags,you could buy with only 5,000 yen [roughly 50 US dollars] any kind of old rags, and I felt like I almost could take them for free. In the end, the rags became a patchwork. It was a waste of cloth, so they made patchwork out of it and used it as work clothes. Because they are poor, they make such things. But…

Chen: But now the price has gone up.

Yoshida: It’s already hundreds of thousands. It’s not in Japan, but in France, the price is about 700,000 yen. It was auctioned the other day.

Chen: What is the purpose of buying them?

Yoshida: They look at them as art.

Chen: Oh my god.

Yoshida: When I first started buying them for almost nothing, for only 1,000 or 2,000 yen from street vendors. They thought they wouldn’t be able to do business with things like this, so they put a low price on them. I also subconsciously thought that Surrealists and Dadaists would find this interesting. In short, it was like Kurt Schwitters.

Chen:: That’s true. It’s a mishmash of all kinds of things.

Yoshida: I’m sure the Dada guys, like André Breton, and others would love to see this. They have similar works.

Chen: Did they made clothing?

Yoshida: No, they didn’t make clothing, but art works. The end result is the same. The Surrealists, for example. That’s why I think my collection is really good if you look at it as a piece of art. I like the fact that it’s not made by an artist, and that it’s made by a farmer’s grandmother in the countryside who has never heard of art or design. These clothes. And today, when Martin Margiela, for example, a fussy designer, sees those clothes, he collects them. It’s amazing.

Chen: Is that true? Margiela collects Japanese old rags?

Yoshida: Yes, Margiela. Margiela was a famous fashion designer, but he sold the Margiela brand a long time ago, and now he’s some sort of archaeologist.

Chen: I didn’t know that.

Yoshida: They collect old pieces like this as well. That’s why Japanese people have the sense that, as I came to understand later, if something is classified as art, it is seen as art. If something is not categorized as art, many people don’t recognize it as art unless they are told so. I don’t know if it’s because I live a rather chaotic life, but when I find this on my own, I think it’s interesting, like the Surrealists. And Beuys always come to my mind, and I wonder what Beuys would say if I showed it to him. I think that’s interesting. But at that time, when I showed it to people, they would say that I was silly for collecting all this stuff, but eventually, about 30 years later, I realized that people like Margiela love this material. There are some famous designers in Japan, who also react in a big way.

So, recently, I’ve been able to sort out all the things that make me wonder what this is all about, and I’ve been able to understand it very well. Starting with Beuys, I’ve been thinking about the things I couldn’t answer the questions about, and how he would have been enjoyed if I had answered them in this way. Everything has a meaning later.

(This interview will be continued in Part 2)

- License:

- CC-BY