My interest in Eurasian culture has been nurtured by a variety of sources. One of the most influential was a series of works by French anthropologist Didier Gazagnadou. I was first exposed to Professor Gazagnadou’s research while listening to a podcast of “Culture d’Islam,” a program hosted by Abdelwahab Meddeb, a French cultural figure from Tunisia, on France Culture radio. I was fascinated by the way Professor Gazagnadou answered questions backed by Mr. Meddeb’s extensive knowledge of the history of Arab culture with great clarity of facts and discretion in answering opaque matters. I immediately ordered a copy of his book. As a graduate student at the University of Tokyo studying the practice of cybernetics theory, I found Professor Gazagnadou’s account of the historical development of Eurasian postal networks very stimulating and inspiring. Conducting back then research on Internet culture, I found the Eurasian postal network to be an archetype of the Internet. I thought that by learning about the history of postal relay, I could understand the nature of networks, which are common to both digital and physical technologies.

Professor Gazagnadou’s book, “The Diffusion of a postal relay system in premodern Eurasia” (Editions Kimé, 2016), describes the history of the relay system, which was passed down from the Song Dynasty (But existing in China since Antiquity) in China to Genghis Khan’s Mongol Empire and later spread to Europe via Italy. It is a book that studies the historical evolution of the technology used to construct relay networks for relay races, which spread from the Song Dynasty in China to the Mongol Empire of Genghis Khan, and later to Europe via Italy, from the perspective of cultural diffusion. The concept of cultural diffusion itself can be a tool for me to understand my own identity as a person with a multiethnic background, and I thought it would be very useful to understand the reality of contemporary Central Eurasia in this EURASIA program.

Therefore, I asked Professor Gazagnadou, with whom I had been communicating only by e-mail and letters, for an interview via Zoom, and fortunately he kindly agreed. The interview covered not only cultural diffusion in Eurasia, but also Japan, East Asia, and France. It was a long interview, so I will publish it in two parts. The following is the first part.

This interview was conducted on two occasions (18th January & 5th July 2021) on Zoom. The author edited the two interviews to produce the following text.

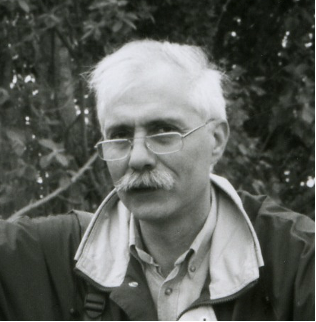

Didier Gazagnadou is a French anthropologist, born in 1952. He is a Full Professor of anthropology (Dr. HDR.) and teaches at the Department of Sociology and Anthropology at University Paris 8 – Vincennes, where he continues his research on technical and cultural diffusion in Eurasia, specially in Iran and the Arab World, with a partially diffusionist approach.

After completing studies in philosophy at the universities of Paris I Pantheon-Sorbonne and Paris VIII – Vincennes à Saint-Denis, Didier Gazagnadou went on to study anthropology. He is now a University Professor in anthropology at University Paris VIII and lead researcher in the laboratory Centre d’Histoire des Sociétés Médiévales et Modernes (MéMo) of Paris 8 and Paris Nanterre Universities. During the course of his career, he was based in Iran on two occasions. First of all in 1993 and then in 1997 (in Teheran), where he was a researcher at the Institut Français de Recherche en Iran (IFRI). He was subsequently posted in the Arabian Peninsula from September 2007 to August 2010, where he worked for the Ministry of Foreign Affairs as Cultural Advisor at the French Embassy in the United Arab Emirates. He is a member of the French Association of Ethnology and Anthropology (A.F.E.A. Association Française d’Ethnologie et d’Anthropologie) and of the “Société Asiatique”.

Dominique CHEN (Dominique):

I read your articles that you sent me after our first interview, and I was particularly amazed by your article on stirrups. I thought when I read it, this is a case that could make my new friends from Central Asia proud.

So that’s why I just wanted to ask you, do you know of any other cases of diffusion that go from nomads to China or other big countries, I would say in Europe or in Iran?

Didier GAZAGNADOU (Didier) :

Honestly, you’re giving me a hard time. But I’m thinking about it a little bit and, as well as the stirrup case is also linked to two discussions, on the one hand with Joseph Needham [* a British biochemist, later turned historian and sinologist, who specialized in the history of Chinese science and technology] himself. And because it gave me ideas, so I plunged into this research to arrive at a disagreement with him, because he thought that the stirrups came from China.

Until now, until proven otherwise. But I haven’t had any feedback nationally or internationally. So I’m still cautious, but until I see evidence to the contrary, I don’t think we’ve found pairs of stirrups, I mean “pairs” of stirrups, because the aid on the side of a horse is, you can find it in India. But it is not the same as a pair of stirrups…

Dominique

It was for ceremonies in India.

Didier

That’s right, so these are the oldest pairs of stirrups that I found by reading the Russians. So will we find others? For the moment I remain with what I have found, that is to say, the dating of stirrups in the regions of Mongolia, two, three centuries before the Christian era. That’s why I leave it at that. I recently watched a documentary on Arte [* French/German cultural TV channel] about Mongolia and horse breeding, and you can see how the Mongolian breeders were dressed at that time.

Dominique

What period are you talking about?

Didier

Ah the contemporary, there it is a contemporary documentary. But I am convinced, in the ancient descriptions, that there is a continuity for reasons of elsewhere, material and climatic. We see the caftan, and the Mongols cover themselves with a kind of large caftans. Besides the word caftan probably comes from this region. And it is quite possible that this type of clothing has spread a little more in Central Asia. The way of putting it on, it’s possible, it’s quite possible that this dress was spread.

Source: Wikimedia Commons (CC:BY-SA 4.0)

Dominique

Is it a diffusion that starts from the nomads?

Didier

So it’s complicated because, I would say, from Upper Asia, from the Mongolian world. But there also Turko-Mongol in the ancient times. These are two Ural-Altaic languages with the same structure, if you like, with common words, but afterwards they diverged to have different pronunciations and vocalizations. But still, there is something in common between, originally very clearly. It is not by chance that the Mongols surrounded themselves in the 13th century with Uyghurs, with Uyghur scholars who already had a script who helped, who are at the origin of the later writing of the Mongols. So there is a cultural community, which does not mean that there are no differences, on the contrary, since I believe that today, even if there are common things, I think that a Turk would not understand a Mongol and vice versa. On the other hand, in the past, there were relations in Central Asia, and in Upper Asia between the Turkish and Mongolian populations, that is clear.

So unfortunately, in other cases of very precise, well followed diffusion of the nomads towards China or towards Europe, I do not have concrete and very precise elements to tell you. There are probably some because, as you know, the populations came nomadic from Central Asia, came to Gaul at the beginning of 5th century, we know the case of the Huns, they arrived-

Dominique

Have the Huns reached France?

Didier

They have reached Gaul, yes. And the detachment that is going until center of Gaul (near the current city of Orléans) !. So from this fact, is that by Attila, and his Turkic-Mongolian groups, that the diffusions started? I’m not sure, because there I have not studied enough the question that-

Dominique

So the Huns were also Turko-Mongols.

Didier

Oh yes, yes, it’s from Central Asia, the Asian peoples of Central Asia. Yes, absolutely. Did they spread at that time, material traits, technical elements through Europe, through Russia, through Europe to Western Europe? It is not impossible. But it requires a really very precise work on which one can, you see all the problem of the study of the anthropology of the technical and cultural diffusions, it is that you must proceed by step, to be very precise. Otherwise we fall into generalities. But okay, the diffusion has to be established.

Dominique

Do you ever talk about assumptions that you haven’t developed well in public places? I guess not, but that’s also very interesting to hear.

Didier

Oh no, that’s not good. No, not really, because… It isn’t that I don’t want to, but in class yes, in seminar.

Dominique

Oh, right.

Didier

In seminar, with Master and PhD students.

Dominique

So can we pretend we’re now having a class, and I’m your student?

Didier

Haha, no! But in this case you see, to be honest, there was another issue in the stirrups. It is this discussion that is not finished because there I do not have an answer, as you saw in the article, a firm one. It is the problem of the introduction of the stirrup in the Middle East and Iran. So I remain with the idea that, at least part of the Persian Sassanid cavalry, the elite of the elite had to have, to be with what is called the cataphractaries, that is to say also heavily armed, had to have stirrups because it is very difficult otherwise to fight on horseback.

Unfortunately, through discussions that I have had in Iran for the moment, we have not found any other stirrups. Except for this famous sculpture in the mountain that I quote in my article, which shows a position, both of stirrups, of presence of stirrups, and above for the Shah or the king, a position without stirrups.

But now there’s a big discussion. Did the Arabs introduce the stirrup, as the great American technologist thought? Would they have borrowed it from the Iranians instead? It’s still a very important discussion.

Dominique

Right.

Didier

And there are still things to establish. Otherwise, it’s not that I want to make assumptions, I suppose that obviously, when the Mongols occupied China, or Iran, I can’t imagine that they didn’t diffuse, without their knowledge moreover, elements to China, and took elements themselves, although they themselves may have been distrustful of the sedentary elites, for political and military reasons.

Dominique

You mean the Mongols were suspicious of the sedentary Chinese?

Didier

I think the Mongols were suspicious. They were suspicious of the populations they dominated, of the elites of the countries they dominated, as in China as in Iran. For political reasons, of course, because they were in the minority in number. But when you’re in the minority, you keep to yourself, and the issue for them was political domination. So not to leave too much power to the elites still in place, who had rallied them, then there is a certain distrust. So for example, the Mongols certainly played a role in the diffusion towards the Middle East, also of material and aesthetic elements.

And in the field of art, it’s very likely, at the time of the Mongol conquest, that a type of painting and miniatures appeared in the Iranian world. If you have the opportunity to go there, you will see in a library very clearly of Asian inspiration, and Chinese. In the way of drawing characters, in the way of drawing faces, in the colors. There we have a Chinese-Mongolian influence, probably in the miniature, and also in ceramics.

Dominique

This artistic diffusion was mediated by the Silk Roads?

Didier

While being well agreed that when we say the Silk Roads, it is an expression, that is to say which evokes poetic images as we continue to use it and which, in our imagination designates relations between the Far East, the Middle East, the Near East, Europe. In one way or another, to one section or another of the Silk Road, that is to say, networks, routes on which caravans, more men than women, have been circulating more or less actively since Antiquity, but women too.

The networks of postal relays established by the Mongols are still there. I have a project of topographical studies in Iran, since I discovered that there were still 17 places and villages bearing a Mongol name, the Mongol name of the Postal relay-

Dominique

In Iran?

Didier

In Iran.

Dominique

You mean they contain the word Yam or Jam in their names?

Didier

Exactly, there are 17 villages called Yam or Yamchi. I went to one of this village called yâmchi, and the people have no memory obviously of what it means, they don’t even know what it means. Next to Tabriz, where the Mongols were settled at the time when the groups, that is to say in the middle of the 13th century. So there are still things to do, there is no doubt. About China, I don’t master Chinese at all, I don’t know China.

The Chinese were also very good with a very developed civilization. Under the Song of the North, when they were invaded, would they have borrowed, perhaps around the cavalry, perhaps around the horse, some techniques? That’s possible, we’d have to dig into that. There is still a lot of work to do.

Dominique

Thank you very much. It’s interesting how there has been this cultural influence from China to Iran. Are there any cases of diffusions going from Iran to China, on the other way around?

Didier

Oh yes, there are some. So here again it’s not worked out enough, but we have the case of, you kindly referred to this article. We have the case of, well, a problematic case, that is to say, a case of diffusion without impact.

Dominique

Oh, right.

Didier

And what is interesting is the case that I develop in this article. I have been confirmed by sinologist colleagues that there are Persian medical treaties in the Chinese imperial library, written in Persian and Arabic.

Dominique

You have found in fact traces of a Chinese man that has been living in Baghdad.

Didier

So it is impossible to say that it is him.

Dominique

Yes, yes.

Didier

But in any case, we find in the Chinese imperial library some treaties in Arabic and Persian of Greco-Islamic medicine.

Dominique

Arabic and Persian documents translated into Chinese?

Didier

Not translated, we found the treaties. So maybe translated later, then you’d have to ask my sinologist colleagues, really specialists in the history of medicine. But what is striking, in one way or another, is that there is no trace of the effect or influence of Greco-Islamic medicine, I say Greco-Islamic because many things were inspired by the Greek tradition, which does not exclude of course an Islamic contribution, but without influence on Chinese medicine and vice versa.

Dominique

There is no trace in Iran, or the Persian world, or the Middle Eastern Arab world, of Chinese medicine. This is what you also write in your article.

Didier

That’s right. But it’s an interesting case anyway, because we see that at a given moment, in the logic of the anthropological study of diffusion. We have to be extremely precise and modest, because we have to follow, you see? It is there, I put forward the idea of a different paradigm, completely different. That is to say, basically, completely different philosophical structures, but it is true that China has a medical tradition that is really very different from the rest of the world, very different from Indian medicine, which also has a very particular, very specific medicine.

So it’s interesting because we see something perhaps borrowed, even from medieval times. But without continuation, it remains there. And then there it is without evolution it is like a dead end. Interesting!

Dominique

There were contacts, but they didn’t last then.

Didier

Contacts that did not give something, that did not produce something. So it’s true, we’re in the field really, by also being interested, it’s at another level, we have a question because it’s first of all the scientific field. But obviously it’s complicated at the time, even if my Arabic text says that this scholar, this Chinese scholar, this Chinese doctor, we don’t know very well, it’s not specified, learned Arabic in a few months, which seems to me a bit doubtful.

Let’s admit, to the point of being able to copy Galen’s medical treatises, it’s certainly exaggerated, but this trace is interesting. But at the level of science obviously, especially in medieval times, today, it’s all, for example, quite different the relationships between scientists. In medieval times it is complicated to understand that the other works within parameters, with totally different paradigms. How to explain, to make understand to a Persian doctor and philosopher, or of Islamic formation, therefore monotheist, that the body is divided in network on which there are points, and that it is the energy, and that all that functions? You see? It is a very interesting case, I think that there are at one point some blockages.

Dominique

I also have to address this theme of religion, because you just said monotheistic. I have been interested in the difference of epistemologies between monotheistic and polytheistic and pantheistic religions. And even in Japan, you see it’s really a country of syncretism. They have absorbed every religion that was imported from the continent, to blend with vernacular proto-religion.

Didier

Well, the case of Japan is already interesting, because Japan is both Buddhist, but at the same time Shinto.

Dominique

Yes, and that integration followed some complicated evolution. When Buddhism was imported to Japanese dynasties in around 7th century, Buddhist logics were seen superior to the existing structures of Shinto. Domestic deities were given Buddhist titles, for example. But as nationalist movement gained power in the pre-modern era, they slowly started to separate the Buddhist influences. After the Meiji Restoration in the late 19th century, when the emperor became the head of state again, they tried to destroy all the Buddhist temples, and restore the Shinto power.

So throughout this history, a very complex process of amalgamation of different paradigms occurred, which characterizes the epistemological reality of Japanese culture.

Didier

Oh yeah, I didn’t know that. I’m also interested in how you differentiate what we we call Shinto places of worship from the Buddhist ones?

Dominique

The Shinto places of worship is called Jinja. Jin means Gods, the same character as Shin in Shinto (which means the way of god). In Buddhism, you call the sacred figures Hotoke or Butsu. And Ja or Sha means buildings, or in ancient Japanese, forest, where the spirits resided.

Didier

I see.

Dominique

At the very beginning, the sacred places in the Japanese proto-religions, the proto-shinto, were really located inside the forests, often in the mountains. The object of admiration for the proto-shinto was really the mountains. This is why they built shrines at the base of the mountains. That’s a totally different concept of building temples and placing statues of Buddha inside them.

Didier

Ah, okay, that’s interesting. I didn’t know, you taught me something, I was totally unaware of this wave of repression with the Meiji, so second part of the 19th century.

Dominique

Exactly.

Didier

I knew it for China, it is well known Jacques Gernet the great sinologist explained it well on the period of rejection of Buddhism and repression in the 8th century, great repression. And what is striking is that Needham as well as Gernet, seemed to say that finally Buddhism was a little bit culturally insignificant, did not really correspond to the Chinese culture.

Dominique

Yes, because it is a very minority religion in China today, isn’t it?

Didier

It’s true, currently a minority. In Japan, no?

Dominique

So in Japan I would say that it is so widespread, that nobody pays attention to the existence of Buddhism. I read a series of censuses that have been done quite recently by NHK, where they asked Japanese people if they consider themselves religious or not. And a lot of Japanese people answered they don’t consider themselves as religious. But what is also striking is that at the same time they somehow believed in religious superstitions, coming from Buddhism and Shintoism.

Didier

Because in Japan, you can see it when you walk around, people walk around a lot in all the temples, in all the places of worship, they like to go there, they like to go for a walk.

Dominique

In fact these are places, I would say, that are quite commercially consumed today. They show on TV a lot of temples, Buddhist temples and Shinto shrines, as completely contemporary tourist sites. And there they use a Japanese-made English word which is “Power spot”. It designates a place where they can feel supernatural force and heal their daily stresses. This has no direct relation to Buddhist or Shinto faith.

Didier

Right.

Dominique

For instance there are a lot of young Japanese people who visit Buddhist or Shinto temples as pure tourists and not devotees. Anyway, these are interesting cases.

Didier

Very interesting.

Dominique

And I asked you this question about religion because there is also another case of diffusions that I am particularly interested in, it is the cultural diffusions that were brought by the expedition of Alexander the Great.

Because in Japan, there is a Japanese philosopher who was active between the beginning and the middle of the 20th century, his name is Tetsurō Watsuji. By the way, there is a contemporary French philosopher who studied in Japan, Augustin Berque, who is a specialist of Watsuji. Watsuji has developed a philosophy of landscape. He also studied a lot the differences and connections between the different Asian religions, in Japan, in China, in India. In one of his famous books that he had written, “Koji Junrei” (Pilgrimages to the Ancient Temples in Nara), he had visited many temples in Kyoto and Nara. And he had tried to trace the exotic influences on these Buddhist statues. And actually it’s not his original idea, I think it’s an archaeological fact that has been studied quite a bit, but there were Greco-Roman influences on Buddhist statues, which is said to be caused by the Macedonian expedition of Alexander the Great that reached the region of Ghandara.

Didier

Ah yes, I see what you’re saying, this question of the Greco-Buddhist statues of Central Asia.

Dominique

Exactly.

Didier

Absolutely. It happened about the time of Alexander, right. Yes, that’s right. As you said, I think there’s quite a bit of work on it. It must have been at the time of Alexander, when there was a sort of fusion of two artistic trends, Buddhist art and Greek art. But I didn’t know that it had spread it to Japan.

But it is quite possible, yes. On the other hand, to come back to your question about religions, monotheism, and here I agree with Jacques Gernet who was really a great man, unfortunately deceased now, holder of a chair at the Collège de France of sinology.

There is a very beautiful book of him called “China and Christianity”. Where everything is focused on, and there it shows something that is quite interesting, that I would say it should touch Japan and Korea. It shows that monotheism is something, and especially that we have all the works of the Jesuits installed in China from the 17th century, before being chased away from China. They were also chased away from Japan under the Tokugawa period.

And it shows that monotheism, and for me this is fascinating, is really a matter of culture. But I will go further with an analysis, even with the use of cognitivist terms which show that there is a kind of incompatibility between the Asian world.

Continue to part 2.

- License:

- CC-BY