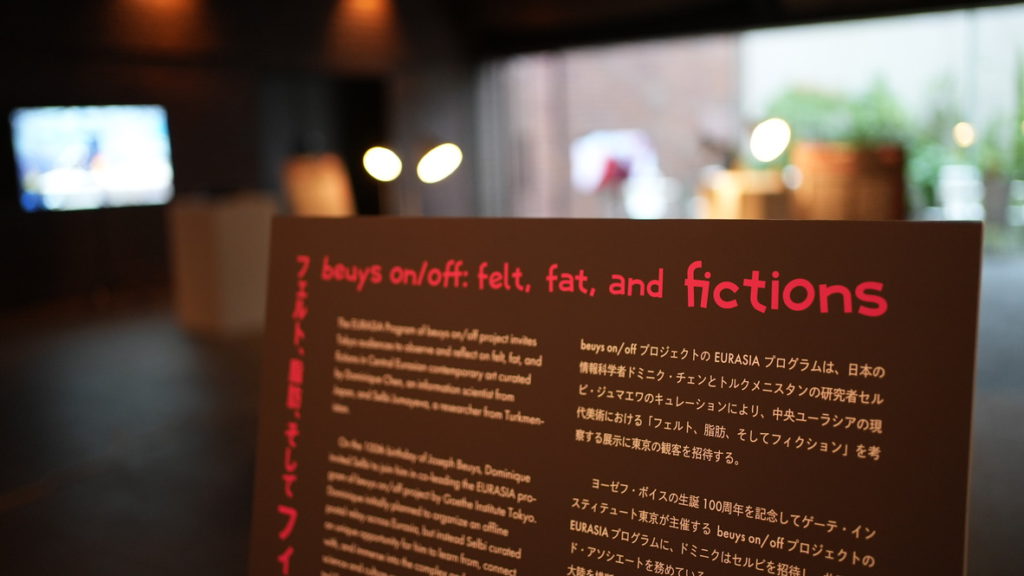

This article looks back at the EURASIA program exhibition “felt, fat, and fictions” that was held at the Goethe-Institut in Tokyo from September 3-5, 2021. The concept of the exhibition and the details of the exhibition, including the introduction of the artists and their works, are described in the previous article, but in this article, as one of the co-curators, I would like to talk with the audience on-site and describe how they faced the works.

Before that, I would like to introduce how this exhibition overlaps with Beuys’ footsteps and how this relates to this exhibition.

The exhibition featured works by three contemporary Central Eurasian artists and a new video work with the participation of co-curator Selbi Jumayeva, installed in the foyer space on the first floor of the Goethe-Institut Tokyo. The cultural institution Sogetsu Kaikan, where numerous artists have performed since 1972, is actually located near this venue, where Joseph Beuys, on his first visit to Japan on June 2, 1984, gave the “Action performance for 2 pianos” with Nam June Paik. In this performance, Beuys played the piano with Paik for about an hour, made animal noises as a coyote, and finally ended the performance with an alarm clock ringing. In the Q&A session that followed, he told an anecdote about how he was rescued by Crimean Tatars when his fighter plane crashed during World War II, and was wrapped in felt and fat and cared for (“1984 Joseph Beuys in Japan,”Seibu Museum+WAVE+SPN, 1984(ISBN-4-89342-025-9), pp.203-204). He said that the use of felt and fat in his work was “just a coincidence,” and that he was not aware of any connection with the Tatars, and that his “theories about heat and sculpture” went along with the Tatars’ “taste for a way of life” that was “very Asian, even Mongolian.

Today, the episode of Beuys’ rescue by the Crimean Tatars is considered fiction, based on verification of military records. Beuys’s cunning in linking felts and fats to Eurasian nomadic cultures in his self-tailored mythology, and then trying to distance himself from it by stating that it happened to fit his theory of sculpture, is interesting. It could be seen as an insurance policy in case the lie would be exposed, but it is more likely that he was trying to strengthen the concept of his own work, EURASIA, by mentioning that the social sculpture theory he had constructed coincidentally corresponded to deep Eurasian culture.

The felts, fats, and fictions exhibition is an attempt to compare and put in contrast Beuys’ vision of EURASIA, and the works of contemporary artists who truly embody Eurasian culture, in this land where, oddly enough, the residue of Beuys’ vision remains.

I was in the gallery every day for the three days of the exhibition, observing the visitors and often giving them explanations. Despite the fact that it rained every day, and the COVID-19 state of emergency declared by the city of Tokyo, the nearby roads closed due to the Paralympics, a total of 165 people visited the exhibition over the three days. In addition to those interested in Eurasian culture, Central Asian artists, or the relationship between Beuys’ work and EURASIA, other visitors included contemporary artists, designers, writers, professors and students at art universities, art critics, researchers, television directors, gallery owners, curators.

In this exhibition, in addition to the works of each artist, texts taken from interviews with each artist were displayed as “fiction” panels. In these panels, the artists talked about episodes in which they confronted the image of Eurasia as seen from the outside of Central Asia (mainly from the West), showed the situation in the art world where the felt material was perceived as if it belonged to Joseph Beuys, or confronted the traditions and history of Central Asia by distancing themselves from the trends in artistic expression. While reading these contemporary narratives, the Japanese audience contemplated the works by the Central Asian artists made of felt, lead, fat, and action, and were surprised to learn about the various realities of contemporary Eurasia that I had learned about in the course of this project. I received so many interesting comments and impressions from the visitors that I cannot list them all.

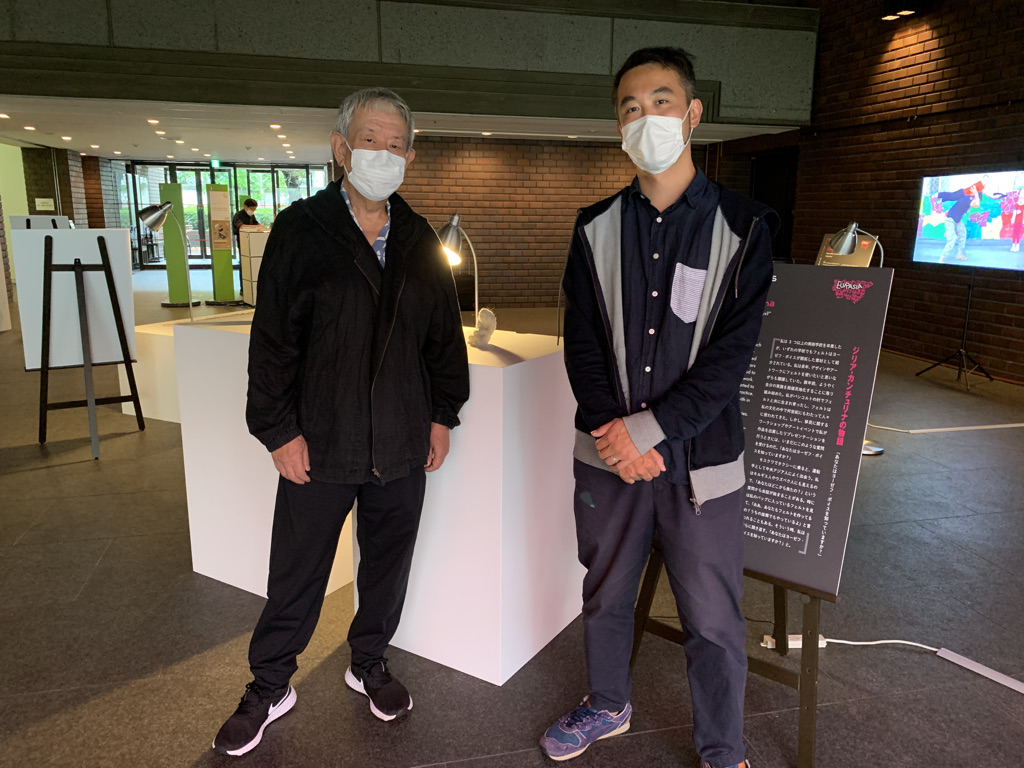

However, I would like to report on one encounter with a visitor that was symbolic for this project. It was the artist Shinichiro Yoshida, whom I interviewed for the EURASIA program. Mr. Yoshida, who is based in Kyoto, came to the exhibition on the first day. We had a long interview with him, but due to COVID-19, I had not yet been able to meet him in person. I also felt that the purpose of this project could not be fully understood from the information on the website alone, so I really appreciated that he came to see the works by Central Asian artists in person. In fact, Mr. Yoshida told me that he was impressed by the works on display and the stories of the artists.

When he saw “Sealing Felt Self” by Altinay Osmoeva, he was surprised to see that lead was melted into felt, and was interested in the cultural connection between “Chi” in Kyrgyzstan and “Sudare” (https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Sudare) in Japan. He also told me that the felt material was similar to the felt used by Beuys. Mr. Yoshida was also impressed by the decolonial meaning of Ziliia Kanchurina’s “Nomadic Body”. He commented that he appreciated the fact that Zillia continued to make these felt sculptures of homeless people as a personal activity, and that once she had about 100 of them, she would be able to produce an even greater presence as a work of art. He also immediately understood the meaning of Chingiz Aidarov’s “Bistrovka-Nabeg” action and praised it as “cool!” He also agreed with Chingiz’ concept and said that it is more important to follow your intuition than to make plans. Finally, while watching the frying of a lump of fat at “Untitled Fat,” we talked about how it reminds of Osaka’s specialty “Aburakasu,” which is made by frying cow intestines in oil for a long time to remove excess oil and concentrate the flavor of the meat, evoking to us the possible culinary connection between East and Central Asia.

As I spent the three days with the works of Altynai, Ziliia, Chingiz, and Selbi, and repeatedly explained the projects and individual works to the visitors, I felt that there were still countless things that I did not know about Central Eurasia beyond what I had learned so far. This time, due to the COVID-19 pandemic, I was unable to actually visit Central Asia and meet the artists face-to-face, which made the whole process especially difficult. Nevertheless, thanks to the faint smell of burnt felt from Altynai’s works, the melancholy of Ziliia’s felt sculptures that make you want to hug them, the various people and landscapes reflected in Chingiz’s action records, Marat Rayimkulov’s humorous yet emotionally complex voice art that overlaps them, and the bustle of the Bishkek market evoked by Selbi’s images of fried fat, I was able to briefly visit the world of my new friends from Central Eurasia.

If Beuys drew on Eurasia for his mythology, he should have gone there and met his contemporaries. He may have had some technical difficulties living in the middle of the Cold War, but we will never know. However, as I was taking down the exhibition after three days, I suddenly felt like showing this exhibition to Beuys, should he be still alive. Selbi told me at one of our meetings that the process of listening to and spending time with people from different cultures is what decolonialism is about. I still haven’t spent any face-to-face time there, so I really need to visit soon. I also hope that this exhibition will be the start of introducing more diverse artworks from Eurasia to Japan and East Asia, as opportunities to see the works of contemporary Central Asian artists in Japan are still rare. At the same time, I was delighted to hear that many of the visitors said they wished to visit Central Asia after the pandemic is over.

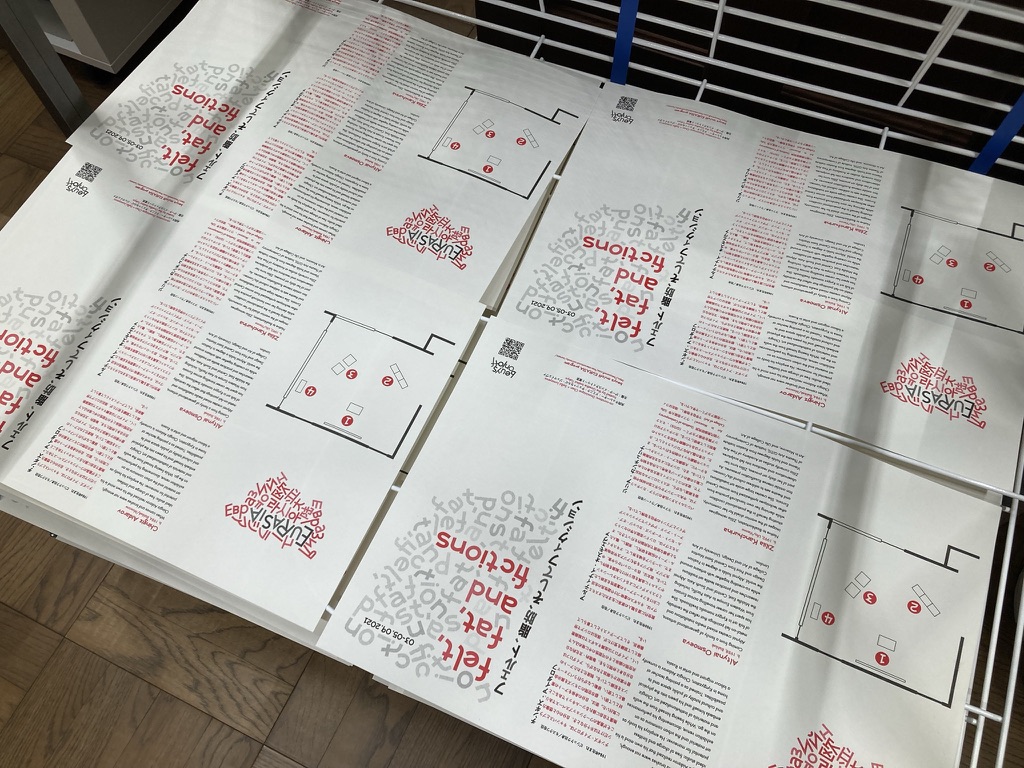

Once again, I would like to express my utmost gratitude and respect to Selbi and the participating artists for guiding me through this wonderful journey. I would also like to thank the Goethe-Institut Tokyo and artistic director Mizuki Takahashi for inviting me on this occasion of Joseph Beuys’ 100th birthday. I would also like to express my special thanks to Mr. Tsukada and Mr. Hidechika of the Dainippon Type Organization for their wonderful graphic design for the panels and handouts, and the Ichigaya no Mori Book and Type Museum for their beautiful lithograph printing.

- License:

- CC-BY