This is the second part of Shinichiro Yoshida’s interview for the Eurasia program. (See Part 1 here)

In this part, Mr. Yoshida explains how he finalized his recent installation of white clothes as an answer to the questions he received from Joseph Beuys in 1977.

The interview was conducted via Zoom, on 10th of February, 2021.

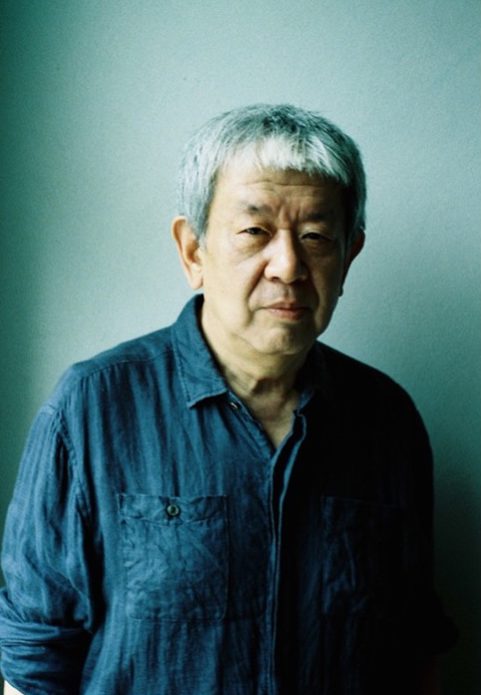

Shinichiro Yoshida

Born in 1948 in Kyoto, Japan. Artist, Director of the Early Modern Asafu (Hemp Cloth) Laboratory. He has organized and participated in various exhibition of his collection of traditional clothes. One of his recent installation is « White » shown at Yamaguchi Center for Arts and Media (YCAM) in 2017. His main publications include the magazine Taiyo Special Edition: Natural Fabrics of Japan”, Heibonsha, 2004, and the exhibition catalogues of “The Cloth that Sustained the Nanto: Nara Sarashi” (2016), “Takamiya Cloth” (2007), “Raw Materials for Nara Sarashi” (2006), “Four Great Linen Cloths” (2012), and “Riches from Rags” (1994). He was awarded the Mizuki Jugodo prize for his outstanding research of Japanese fabrics.

Chen: At YCAM in Yamaguchi, you used the name “white” and covered the walls with a massive variety of white cloths. Maybe that was your answer to Beuys’ question about why you use white paint on white canvas?

Photo credit: Kazuomi Furuya. Courtesy of Yamaguchi Center for Arts and Media [YCAM]

Yoshida: That’s right. That’s why, for me, after I came back from Germany and met Beuys, there was no point in selling or presenting my work unless I settled that issue. So, as Beuys said, selling doesn’t mean anything, and I agree. I think he said it very well, but for the first 20 years since I came back to Japan, I was wishing that I had never met that guy.

Chen: Does that mean that you couldn’t draw anymore because of what he said?

Yoshida: Everything became a mess. I couldn’t paint anymore, and my plans to make a living by painting have been ruined. That’s why my life itself was also ruined. That’s why in my 30s and 40s, when other people are most active, I was really suffering. I faced my work every day, but in the end, I couldn’t settle it within myself. It’s easy to make work. That’s a strange way of putting it, but if you want to make a work, you can.

Chen: So you were just not satisfied?

Yoshida: No. I was hearing the voice of Beuys again. “What’s the point in that?”

Chen: It’s like the curse of Beuys.

Yoshida: It’s like a curse. When I think it works, and it’s okay, which is cool from a design point of view. But it doesn’t make sense as art. When that sort of thought comes out again in my mind, I burnt the work again. I destroyed it.

When I was doing that, when I was living in Tokyo, I didn’t have a lot of money, and I didn’t have any other place to live, so I threw away and burnt things that had no meaning. If you live in a big house, you might want to keep some things. It’s hard to store things in Tokyo. People say, “Let’s keep only the things that have meaning,” but I couldn’t make anything that had any sort of meaning.

Chen: That was after you came back from Germany.

Yoshida: After I returned.

Chen: You returned to Japan in 1977, right?

Yoshida: Yes, I was 27.

Chen: So from that point until the mid 1990s, you were collecting fabrics while making art?

Yoshida: Yes, yes. I was already doing cloth. Then, to come back to the topic at hand, I decided that I was going to show my work to Beuys when I would have collected about 100 pieces of cloth, and made a piece of art. I was looking forward to what Beuys would say when I showed it to him, and I said I would come back. After I made them, as I mentioned earlier, I examined them under the microscope and found various fibers, and I was hooked on that for five, six, maybe seven years. I was hooked on it, and that’s all I did. I was thinking, I would stop collecting clothes once I would figure out the raw materials for Japanese clothing, and make that work.

But in the middle of that, when I was about 43, when I was a little over 40, a curator from a museum in San Francisco [Dai Williams] came to see me.

Chen:: That lead to the Riches from Rags exhibition.

Yoshida: Yes. At that time, the Japanese way of thinking was considered very advanced, and they were very keen on the idea of recycling.

Chen: There are a lot of references to recycling in your book.

Yoshida: So, that was the theme of the book, but in the end, if you want to know what kind of lifestyle the Japanese people had, you have to ask what kind of raw materials they used to make their clothing and lifestyle. So he came to see me. I did some research and told him that there were more than ten different kinds of threads. He asked me to show them to him, and when I did, he said, “Let’s have an exhibition with them,” and so we did. So we had an exhibition, and we made a catalog, a book.

Chen: This was in 1994.

Yoshida: Then it didn’t get any attention in Japan. But in the US, it was quite popular.

Chen: I see.

Yoshida: That’s pretty much how it went, and when it became a hot topic in the US, Japanese museums would come.

Chen:: I see. You were recognized overseas, and then only after that, Japanese museums were interested in your activities. Very typical structure…

Yoshida: Yes, yes. When it became a hot topic overseas, they wanted to talk to me. So he asked me to do it too, and I’ve done exhibitions in about ten museums and art galleries in Japan.

Chen: Is it like a traveling exhibition? Or do you do them individually?

Yoshida: No, it’s not a touring exhibition, I don’t do the same thing twice, I refuse to do the touring exhibition, and each time I do an exhibition, I don’t extend what we’ve already done, so I did about ten exhibitions. And before I knew it, I was being treated like a fabric researcher. No one thinks of me as an artist, and I don’t say I’m a painter. But I’ve been working in museums and galleries for a long time, and even when I started working in Japanese museums, the words of Beuys were still echoing in my mind.

Chen: What did you think? Do you feel like you’ve been liberated from the curse of Beuys by the recognition of your research on clothes?

Yoshida: No, that’s the reason why, in the end, even when I had an exhibition at a museum in Japan showing cloths from the Edo period to the Meiji period, I would have done it with a sense of art, but no one would have come to see it as an art exhibition. It was like an exhibition of kimonos from the Edo period.

Chen: Something like natural history.

Yoshida: I didn’t have to say anything about it being art, and I didn’t say anything about it, but in my mind, all the acts are not finished at all. It’s an extension of Beuys.

Chen: Does that still continue up to now?

Yoshida: Even now, even now, I haven’t lost it at all. One time, I think it was the seventh time. One time, I think it was the seventh time, I did an exhibition at a museum somewhere, I think it was in Tokamachi. It took about a week for the exhibition to be held somewhere, and in a preparation room, all the cloths I brought were piled up in one place, and I was asked which ones to put up like this and which ones to reject. At that time, when I was arranging the white kimonos, there was a strange feeling while I was looking at them blankly. When I looked at each of the kimonos, I saw that I too had white cloth and white kimonos. When I look at each kimono, I see a white cloth, a white kimono, and when I ask people about it, they say that this is a white kimono. It was white. However, when I was preparing in the preparation room, there were 50 to 60 kimonos lined up in a row, and there were only two or three kimonos that were completely white, but when I was laying them out, the ones that I thought were white were not the same white. When I noticed and looked at them from that perspective, I found that the kimonos that I thought were white were not the same white. I thought, “This is what I’ve been searching for.”

Chen: So that’s what you thought at that time?

Yoshida: Yes. That’s when I thought. I thought, “Isn’t this it?” Up until now, I’ve been making collages, expressing myself with paints, and painting, but it doesn’t matter whether I’m painting or drawing. I said, “Why not?” It’s not about something I made anymore. I could just take pieces of cloth from the museum and hold a regular exhibition of the Edo period, just in time for the exhibition. I was so confident, I didn’t care what I had to do, so I just laid out the cloth for about three days. I had about 20 pieces. Then I realized that it was the same white painting I had been aiming for, the one I had done when I was with Beuys. I realized that this was what I wanted to do.

Chen: That’s amazing.

Yoshida: So I kept experimenting, and I thought, “This is it, this is what I’ve got.” At that time, Beuys was already dead. I wasn’t interested in galleries, and I wasn’t interested in the Japanese art scene at all, and I was thinking, “Well, it’s settled in my mind.” There were some galleries that wanted to sell my drawings, but I had never shown them my white paintings. So it was like I was living two lives, and suddenly, there was a man named Inaba, a doctor at Tokyo University, who came to see me and said he wanted to meet me. He had a friend who had made a film about Beuys.

Chen: Mr. Shinya Watanabe, I think.

Yoshida: Yes. I did’t know him at all, I’ve never even met him. And I’ve never met the doctor from Tokyo University either. He came out of nowhere, and was at the Uplink in Shibuya, where I live, I think. He told me to come and see it, because it was going to be held at a small movie theater there. And then he wanted me to tell him what I thought. I told him that I didn’t know Beuys very well, that I didn’t pursue him in detail, that I had only met him, but he said, “No, that’s okay, just come and see the film. So we went to the restaurant after watching the movie, we had dinner and talked about various things about Beuys. The things Beuys said to me.

When he was making sled with felt wrapped around [“The Sled”, 1969], I always thought that any sled would be fine for this purpose, but now I think that the old antique sleighs he chose have good taste. So, when talking about art, you would think anything is fine as long as it’s a sleigh, right? Normally. A beautiful sled would be fine. However, in his context, the sleds he chose are very old, shriveled, and with good taste. He would wrap felt around it and put it out. When we talked about this, I wondered what he meant. When I was talking to Beuys, he would say, “Why honey, why butter?” He used to sign potatoes for me, too. So, Beuys would sign it, in no time at all, while I was walking, with a magic marker. It’s a potato. When I was talking to him, I remember hearing about the World War II, and how he was shot down by the Soviet Air Force. After seeing the movie, Watanabe told me that it was all a lie.

Chen: Yes, it is. It’s said to be a myth.

Yoshida: Apparently. I didn’t know that.

Chen: It is said he wasn’t actually saved by the Crimean Tatars.

Yoshida: That’s what they say, and I said to Watanabe, “What makes you say that?” I told him that I believed it, and he said, “No, it seems to be a myth.

Chen: Right.

Yoshida: He wanted to ask me what I thought about that. When I heard that, I thought it was interesting. I thought it was interesting to imagine that Beuys, after he was shot down, was put on a sleigh.

Chen: And then he was wrapped in felt.

Yoshida: I believed the story that he was wrapped in felt and had butter and honey or something smeared all over him, but when I heard that it was all a myth, I fell in love with Beuys even more.

Chen: That’s interesting. Why is that? Didn’t that make you angry?

Yoshida: No, I didn’t, because in Japan, it’s like the Nihon Shoki or the Kojiki [oldest mythological books of classical Japanese history]. Even the Japanese gods came out of rocks like this. Myths are all the same, aren’t they?

Chen: That’s true

Yoshida: Mythology. When you say a “lie” it sounds like a very bad thing, but I’m amazed that people have created such mythology. That’s why I said it was really interesting. I said that I thought Beuys was really something special.

Chen: But on the other hand, it makes me think of why Beuys asked the young Yoshida-san what your roots in Japan had to do with what you were making. Because Beuys himself created his own roots in a sense.

Yoshida: Yes, yes, yes. But when I look at the my 50 years after meeting him, I realize I circled around the first white I was painting again.

Chen: I understand.

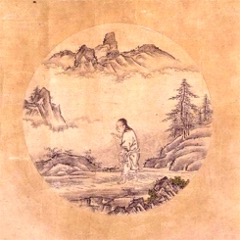

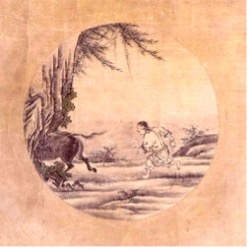

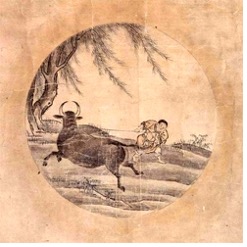

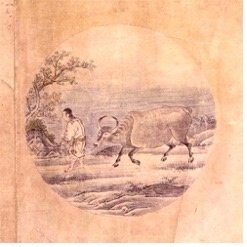

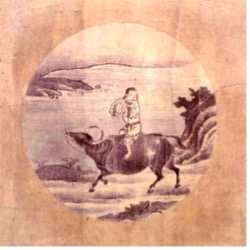

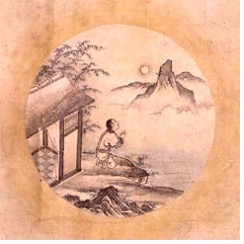

Yoshida: There is a Zen teaching picture [Ten Bulls or Ten Ox Herding Pictures] that compares the cow to the purpose of life, and I remember seeing it in the past. It seems to me something like that.

URL: https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Ten_Bulls

Chen: The process you went through after you met Beuys?

Yoshida: After I met him, yes. At first, I don’t know much about the Ten Ox Herding Pictures, but I was interested in it, and when I looked it up, the first thing that came up was the cow, and the purpose of life is to find the cow. So you found a purpose to do something. The third picture shows that he went out to find his purpose, and this time, he caught the cow. You catch the cow. That is to say, I somehow caught the purpose of my life that I was trying to achieve in my own way, and I caught it. Now, the cow that you caught is able to escape. It escaped. In the end, it’s a Zen teaching, but in the end, it’s all blank again.

Chen: There is a phase of becoming blank, isn’t there? The 8th Figure.

Yoshida: Yes. And the beginning and the end are the same. At the end, there is the same figure as when you are looking for the cow.

I think my story of white is the same. For that thing, the figure may be the same, but it’s the same as the first picture this time, beyond the process of the bull, finding the bull, catching it, and having it run away.

Chen: I see, I see.

Yoshida: That’s what I’m talking about.

Chen: So that’s where you’re coming back to now.

Yoshida: Yes, that’s right. That’s what I was thinking. Now I get it. I wonder what it means to be able to understand things in the end. For example, in human relations, there are people who are suffering from distress. As I listen to them suffering, I can classify them into different genres, and I can say that this person is thinking this way because of this, this, and this. The person who hears this says, “I see, this is how it is, this is white. That is why the current society of human beings, as well as the international society, is the same all over the world. Not only in Japan. It’s not only in Japan, but everywhere. When you answer, “This is this,” or “This is that,” for example, if it looks like the color white, you settle for white.

Chen: I see.

Yoshida: When I first exhibited 50 to 100 kimonos from the Edo period, antique dealers and people would ask me, “I have a white kimono, would you like to see?” And I’d say, “Let me see it.” And I got more white kimonos. However, when I did the work at YCAM, I did exactly the same thing, and it was a large work with 54 pieces, but it was always white from the Edo period. And I also related them the Torihama shell mound. There were fibers of hemp, and there are fifty or more cases of white cloth alone, and no two are the same. When fifty or so of these cloths were displayed in a large venue that is roughly 20 meters long, there is a strange sense of white in the air. In my mind, as an art form, it would work, but now, from the point of view of what Beuys meant, when he said that there is no such thing as the same white, I see the same thing in the comments of people who say they understand, that they can understand, that this is like this, that this is like that. This is not the way to understand each other. Absolutely not. We will never be able to understand each other. It’s always going to be a parallel line. The one who says he understands does not understand either. Even if you want to be understood, even if you throw out a desperate message that you want to be saved, that message will not reach the other person. But they think they have. They think it’s white. But if you really try to save the white by replacing it with that person, it’s just like the exhibition at YCAM. You know the meaning of the displaying the fifty different kinds of hemp. The reason why there are no identical whites is that some are woven with thicker yarns, some with thinner yarns, some with twisted yarns, and some with untwisted yarns. The white is white, but it is the same as the sled used by Beuys. But not only that, as I said before, there is a difference between weaving with thick and thin yarns, yarns that have been twisted and yarns that have not been twisted. The light shines on them, and when we see them, we simply recognize them as white cloth. Applying this to me, as a human being, and to all the peoples of the world, if the problem is to be able to share and truly understand each other’s worries and pains, I believe that if the same thing remains, if we can’t have a conversation, we will never be able to solve the problem, and we will never be able to understand each other. That was the message I threw out at YCAM.

Chen: I see. That’s a really powerful concept.

Yoshida: So I finally thought there, if Beuys was still alive, I would have liked to have this conversation with him. I’d like to hear it, but he’s gone now, you know.

Chen: But that story is quite relevant, if we go back to Joseph Beuys once more. Because Joseph Beuys also elaborated his idea of social sculpture, and that everyone is an artist, and everyone is an expressionist. Joseph Beuys himself was a superstar in the small world of the art, for better or worse. I think he was trying his best to break through the stagnation of the art world. In this context, if Beuys were alive today, I feel that the fact that Yoshida-san continued to collect white clothes and various other fabrics for decades would be connected to Joseph Beuys’ idea of the role of the artist as a social sculpture. I thought that you reached a point to embody Beuys’ dream of social sculpture as an utopia.

Yoshida: No, no, no. So in my case, I’ve lost all connection with the art scene.

Chen: That’s right.

Yoshida: The general public, the general art fans who come to YCAM, don’t understand that at all.

Chen: Is that so?

Yoshida: They didn’t understand me at all, and just a few contemporary art artists praised me a lot, but not much.

Chen: I thought it was the other way around. I can only imagine though. When Japanese people who don’t know anything about contemporary art see those 50 pieces of white cloth, I think they will reflect upon their own roots and the history of Japan.

Yoshida: That’s what I’m hoping for, and that’s what I was expecting to talk about. Especially for the older contemporary art artists, they get it, but I was hoping that some of the younger people would catch on, and that’s why I came here, but there wasn’t any.

Nobody commented on the meaning of white. That’s why I was waiting to see if someone would naturally feel that way, but in the case of Japan, you have to say it.

Chen: It’s like you have to make it explicitly into information.

Yoshida: You have to make the information available, yes.

Chen: Can I ask you one last question? I know it’s a difficult question, but the Goethe-Institut gave us the theme of Eurasia, and that led me to a Koan-like question about how to interpret the performance “Eurasia” that Beuys and Nam June Paik did together. I’ve been doing a lot of research on Eurasia, and you mentioned food, clothing, and shelter, and I’m also researching food, clothing, and shelter in Eurasia.

Yoshida: I see.

Chen: And since you’ve been in contact with Beuys himself, I thought it would be a good idea to talk to you today.

Eurasia is a myth that Beuys created and attributed to himself, right? The existence of the Crimean Tatars. In other words, he tried to connect the nomads of the steppes and the Germans of Western Europe. In Shinya Watanabe’s film, there’s a strong emphasis on this. Beuys left behind a lot of mysterious installations and performances. That aside, I think Eurasia is actually a very interesting theme, even from the point of view of modern people who have nothing to do with contemporary art. But the fact is that, I don’t really understand what is Eurasia, I can’t grasp well its shape or contour, as it covers such a huge territory. This grouping of Central Asia, Europe, and East Asia is quite vague and unintelligible to me.

Yoshida: I know what that is, but Beuys has been saying the word Eurasia a lot since then.

Chen: Did he also talk about it when you were with him?

Yoshida: Yes, he did.

Chen: Really?

Yoshida: Also, what I remember hearing a lot was that Beuys, maybe not directly, but the people around him, the people around him who were attached to Beuys, talked about Eurasia.

Chen: Really? What was the context in which you were talking about Eurasia?

Yoshida: It wasn’t directly from Beuys, but anyway, there were two words that left an impression on me, and the other one was “revolution.” I heard it every day, every day.

Whenever he was talking about something, the word “revolution” was always attached to it.

Chen: That’s one, and the other one was…

Yoshida: Eurasia. It was something like a routine story of Beuys, you know? So I don’t really understand what Eurasia is either. I had been working with the people from the Metropolitan Museum of Art for a long time, maybe 25 years ago. We drove along the Silk Road from Khotan, Kashgar, so through Kazakhstan, Uyghur Autonomous Region to the end of the Silk Road in a raggedy car for about two weeks. I went to see the mummies of the Han Dynasty in China, about 1,500 years ago, because they had been excavated.

Chen: Did you go there, Mr. Yoshida?

Yoshida: Yes, I did. The Metropolitan Museum of Art had a mummy from China that had come out in good condition, still wearing Han Dynasty clothing, and they invited me to go see it.

In hindsight, I had never thought of it as part of Eurasia, but when I went all the way around there, with the guys from Metropolitan, I thought this is one aspect of Eurasia.

Chen: That was right in the middle of Eurasia.

Yoshida: Right in the middle. I don’t know what it means, but when I went around to places like Khotan, Kashgar, Kazakhstan, and so on, I thought as an extension of China, but it’s not China at all. Everywhere I went.

Chen: It’s very different. From the spoken languages, and other aspects.

Yoshida: In that context, I was thinking of clothing, but it was no longer about clothing alone, but the silk fabrics of the Nara period (710-794) and other things from that time period that came into Japan through the Silk Road.

Chen: So silk came to Japan from the Silk Road.

Yoshida: It came in. In the end, there are things left in Japan that are not in China or anywhere else in the world, not even in Chinese museums. That is the Shosoin Repository in Nara. Every year, when the National Museum in Nara holds the Shosoin exhibition, they always display the artifacts, including clothing, that came through the Silk Road. Japan is the only country that keeps such things.

Chen: Only in Japan?

Yoshida: They don’t even go to China. That’s why.

Chen: When you actually went to Kazakhstan, did you collect any of the local fabrics?

Yoshida: No, I didn’t find any of the old ones.

That’s why I wondered why Japan has preserved so many old things. I talked about this in China as well, and the professors at the Chinese universities wanted to do research on old rags, so we looked into it, but there are none left.

Chen: What a waste.

Yoshida: All of the royal family’s artifacts and all of the other artifacts belong to the people in power at the time. But strangely enough, in Japan, there are no promises, laws, or rules about who should keep what, but despite that there are still many things left. Things from the Edo period. I thought it was strange.

Chen: It is strange. Why is that?

Yoshida: I don’t know why, but I’ve been collecting things for about 30 years, maybe 40 years. I’ve been collecting things for a long time, and now I’m doing research on them, but I think there would be more if I went to China, or Bhutan, or Kashgar, but there are none. I wonder if they will all be burned or thrown away. Or both.

Chen: I wonder if they’re going to decay.

Yoshida: That too.

Chen: Also, is there a difference in materials? Like silk tends to deteriorate faster?

Yoshida: If you think about it deeper, you might be able to see something.

Chen: Also, I wanted to ask you one more thing: silk and cotton came to Japan from the continent. I think you wrote that cotton was also difficult to grow in Japan, so it was not before the Edo period Japanese people got accustomed to cotton. Silk also originally came to Japan as a cultural asset from overseas, rather than from within Japan.

Yoshida: It came from China, originally.

But silk has been used since the time of Himiko [Himiko (卑弥呼, c. 170–248 AD), also known as Shingi Waō (親魏倭王, “Ruler of Wa, Friend of Wei”), was a shamaness-queen of Yamatai-koku in Wakoku (倭国, ancient calling of Japan by the Chinese dynasties).], actually.

Chen: That’s right. It came from the Tang Dynasty, right?

Yoshida: So it’s been done since ancient times, but it must have been introduced.

But to be precise in terms of research, they were cultivating hemp in the Torihama shell mounds 10,000 years ago, and before they said they were using hemp or using the fiber, where did the hemp come from? The Torihama Shell Mound in Fukui Prefecture is 10,000 years old, and fragments of hemp have been found in ruins that are clearly 10,000 years old. So I think that’s a big deal when it comes to understanding something.

Chen: That’s right. On the other hand, for example, are there any hemp cloths or hemp garments that you have discovered in the area west of China? Something old?

Yoshida: I don’t have any, but there is something like hemp. Even in China. But as you know, museums and art galleries can’t inspect them for destruction. In the end, you can’t make a determination without looking at it under a microscope. There is nothing there at all to be seen with a loupe.

Chen: You can’t identify the material.

Yoshida: Yes. That’s why we found things like hemp, even when we were on the Silk Road with the Metropolitans, but it was like 1,500 years old. In other words, from the Jomon period in Japan, 1,500 years ago seems like just a few days ago, so we don’t have much time left, but it’s the Han Dynasty, right? I was shown the old hemp at the museum in Uyghur, but I was not allowed to pick up even a few centimeters of thread for a destructive test.

Chen: I see. So you can’t be sure.

Yoshida: If you can’t determine it, you can’t tell whether it was Choma, or Choma, or nettles, or even the banana-like Basho that we still have in Okinawa. Because the appearance is the same as far as the naked eye is concerned.

Chen: I see.

Yoshida: We did microscopic examinations, and in the end, in Japan too, the reason why I had to collect so many pieces is that the collections of museums and art galleries do not allow destructive examination.

Chen: So you can’t study them?

Yoshida: Yes. And the same goes for the Folk Art Museum in Komaba. There is a very good collection at the Folk Art Museum that was collected by Muneyoshi Yanagi, but all of the hemp kimonos, not only at the Folk Art Museum, but also at all the other museums, are all made of hemp. All of them together. That’s why even the exhibition of Edo-era kimonos is made of linen.

Chen: I see. So you don’t know whether it’s kudzu, rattan, hemp, or choma.

Yoshida: No, I don’t know if it’s kudzu or hemp, but there are three types of hemp: choma, nettle, and hemp. Originally, flax is linen, and as you know, linen is a type of hemp, but it was introduced to Japan after the Meiji era. For spinning. It’s a fiber that has nothing to do with Japanese culture. Not since ancient times. In Japan, there are three kinds of hemp: choma, hemp, and nettle, but only in Japan are shirts like this called hemp.

Chen: Is that so?

Yoshida: Whenever I go to Europe, when I wear a shirt, it says 80% linen, 20% hemp, 30% ramie, etc. Ramie, hemp, and linen are completely different types. Only in Japan, you find 100% hemp.

That’s why you can tell when you go to buy a shirt. If you go to Isetan department store, if you look at the hemp shirts, if they are made in Japan, they are written as 100% hemp.

Chen: It’s hard to tell if it’s ramie or hemp.

Yoshida: That’s how it is. So they write “100% hemp,” but when I examined the Isetan shirts with the microscope, I found that they were linen. Flax. It’s neither Hemp nor Choma.

Chen: So you’ve figured it out.

Yoshida: That’s why only Japan is ambiguous. The National Museum in Ueno exhibits it as linen.

It’s very ambiguous. I told the curator at the National Museum. The National Museum is said to be the best museum in Japan, and I told them that this is not good. When I told them that they had to make it clear whether it was hemp or choma, the Japanese government told them that the national museum was funded by taxpayers, so they couldn’t inspect it.

Chen: That’s ridiculous.

Yoshida: That’s ridiculous. That’s why everything is said to be made with linen. If you go to the Ueno museum and look at hemp kimonos from the Edo period, you will see that hemp is no longer used. Now, hemp is no longer available. That’s why if you want to know about the Edo period, you have to collect and study such things freely by themselves. That’s how it became clear. There are many kinds of fibers. Anyway, Japan doesn’t investigate the basics.

Chen: Mr. Yoshida, it was very interesting that you mentioned that Joseph Beuys was interested in Eurasia, and that you thought it was a great achievement that he created his own mythology. Now that you have arrived at hemp, do you have any plans to study Eurasian cloth, for example, in Asia other than Japan, such as East Asia or Central Asia, even if it is completely separate from Beuys or Japan? Are you thinking of doing research on Eurasian fabrics?

Yoshida: I’m not going to go as far as researching this, but for example, there is a design called kasuri in Japan.

Chen: Kasuri.

Yoshida: Kasuri came from Ryukyu before it was introduced to mainland Japan. It’s Okinawa. At that time, Okinawa was not a Japanese country, it was called Ryukyu country during the Edo period. The Ryukyu Kingdom became independent, and Ryukyu had a strong relationship with China, but it traded not only with China but also with Southeast Asia at that time.

So, first of all, kasuri and other such designs and weaving methods were introduced to Ryukyu. Then, what came to Ryukyu became Kurume kasuri and Kyushu kasuri, which in turn came to Nara and the mainland, and then to Honshu, and so the kasuri pattern spread. However, just tracing the roots of the introduction of kasuri, we can see that there has always been trade from Southeast Asia. There is also the weaving of kasuri in Kazakhstan.

URL: https://commons.wikimedia.org/wiki/File:Kimono_from_Okinawa,_Honolulu_Museum_of_Art_14188.1.JPG

Chen: Really?

Yoshida: If I look into it further, I don’t know if there is such a thing called kasuri or not. I don’t know about Europe, but when you think about it in the context of Eurasia, as you mentioned earlier, and about clothing, and the patterns, uses, and designs of clothing, if you go back in time to the past, I think it’s possible to find the relations throughout Eurasia.

Chen: Another difficult area is the south. The Silk Roads of Southeast Asia and Central Asia are quite different.

Yoshida: They are also different.

Chen: But there may have been exchange between them.

Yoshida: But in the old days, kasuri, the weaving of threads dyed first and then woven horizontally and vertically, can be seen in many countries on the Eurasian continent. It is old. So, it must have come from somewhere, and there must be a connection.

It may take some time, but if there is a group of people who are interested in this kind of thing, if you follow them, you may be able to catch something.

Chen: Thank you very much.

One more thing. You just mentioned the keyword “dyeing,” for example, indigo. Indigo dyeing is also found in many places in Eurasia, and of course they are not the same as Tokushima indigo in Japan. On the other hand, do you know of any designs or production methods that flowed from Japan to Eurasia or the continent?

Yoshida: I don’t know if they went to Eurasia or not, but the designs of Louis Vuitton bags are from the Japanese crests, aren’t they?

Such things, and although the times may be a little different, they still have an influence on France and other places, don’t they? Kimonos, for example.

Chen: Yes, in the 19th century.

Yoshida: Not since ancient times, though.

Chen: That’s why they didn’t go through Eurasia, but went directly to Europe by ship.

Yoshida: That’s right.

Chen: So, before the development of ships, shipping routes, and airplanes, Eurasia was a land route that had to be passed through. That’s where many things came from.

Yoshida: That’s right. That’s why I feel that the Silk Road is closer to us.

That route. So I didn’t go all the way to Europe, but I did drive a truck all the way to that area, and it took me two weeks to get there.

Chen: Thank you very much. Finally, could you tell me about the exhibition when you came up with the idea of using white cloth in Tokaichi, and arranging them in a room?

Yoshida: That was the exhibition titled “The Four Great Linen Fabrics – Echigo-shunyu, Nara-sarashi, Takamiya-nuno, and Ecchu-nuno: Threads and Weaving”.

Until then, there was no specific place of origin for hemp. But in this exhibition, we showed the clothes by their origins, such as this is Nara, and this is Echigo, which is now Niigata. This is the hemp from Etchu. The name “Etchu” refers to Toyama. I did an exhibition of Edo-period hemp that specified each region of origin.

At the time I was experimenting, it was during a big art festival. It was a famous art biennale, and as part of the biennale, I was asked to do an exhibition on the Edo period, so I accepted. So I didn’t say anything, and just did a normal exhibition of Edo-period pieces, but downstairs, in the lobby, there was a row of contemporary art works by contemporary artists using half-baked cloth. And then, in the plazas and fields around Tokamachi, they were using cloth and saying that this was contemporary art. I won’t comment on whether it was good or bad. The art journalists came to see them as art. I didn’t say that mine was art, but it was exhibited at the Tokamachi Museum. But if you were Beuys, you don’t need to call it art to get people to come and see it. I see it as art. I see it in the context of art. But in Japan, the audience that comes to see it can’t see that unless they are told so. Because I didn’t advertise my work as art. But I wonder if the people who organize biennales, critics, art reporters, etc. don’t feel anything about it.

Chen: That’s a poignant message to the art world.

Yoshida: So I thought, “If I don’t mention the genre, you guys won’t notice?” So, unless there is a movement of art somewhere, you can’t catch it as art. If you think about it, there is no way that Japan can create a contemporary art scene that is not considered as a genre of art by the world. It’s impossible. But the way people like Beuys in the U.S. or Europe see things, they are not interested in art from the start. In the end, they just see it, and while they are doing something, the people around them create one meaning of art. So some of my works didn’t start out as art, and some of them did, but it doesn’t matter.

Chen: You’re right. Whether it’s Dada, Surrealism, or Fluxus, they all started out as anti-art in some ways.

Yoshida: Yes, yes. So if it’s not called art, people don’t see it as art. That biennale, that’s why I thought it was interesting. I was approached by the biennale, so I did an exhibition at the Tokamachi Museum.

Chen: It’s a pity Beuys couldn’t come see that as well. If he was still alive.

Yoshida: That’s right. In Japan, there are very few people who can grasp art from a blank slate without passing on information. Maybe they don’t exist. That’s what I thought. This is a problem for this country.

Chen: Thank you very much. I think that was the question that Beuys himself posed at the end of his life. Thank you very much. I really appreciate it, and I’m sorry I’ve gone way over the scheduled time.

Yoshida: No, sorry it’s not a coherent story.

Chen:

Thank you very, very much. It’s been about two hours now…

Yoshida: It was fun, it’s been a while since the last time I’ve talked like this. Art comes out from time like this.

Chen: I think so too.

Yoshida: Beuys was exactly that kind of person.

That’s why I was curious about him for a long time, and there were times when I almost gave up on him. But when I thought about him on my way home from Watanabe’s film, I thought to myself, “I’m beyond the age of Beuys when he died.” I suddenly thought. At that time, I was approached by YCAM.

Chen: So that’s what happened.

Yoshida: I felt like I had a connection with them, so I decided to give it a try this time, and accepted their offer and presented it with a white piece I’d already been working on. Then, I was asked if I would like to do a tour of the exhibition, but I won’t do that anymore. I said this would be the first and last time.

Chen: No, I’d like to see it very much. I want to see the real thing. Someday, hopefully. I’m looking forward to another exhibition, not a tour, but another project.

Yoshida: Yes. I’m sorry, I don’t have a coherent story.

Chen: Thank you very much for your time today. I look forward to working with you again.

Yoshida: Thank you.

Mr. Yoshida’s story of moving into the world of traditional craft from fine art, and finally realizing an installation constituted of numerous old white clothes, is symbolic of Beuys’ concept of expanded notion of art. I was especially amazed by his sincerity as an artist who confronted Beuys’ question for more than 40 years, while not producing any new work. He has focused on collecting and analyzing the difference of various types of traditional fabrics of Japan, and became a researcher of the field. Somehow, his journey made me think that if Beuys was still alive, he would have admired Mr. Yoshida’s achievement.

After my interview with Mr. Yoshida, I visited a retrospective exhibition of Beuys and his student artist Blinky Palermo, held at the Toyota Municipal Museum of Art (2021.04.03-2021.0.6.20). This was not my first time of seeing actual works of Beuys, but this time, I was looking at them with a completely different perspective, while reminiscing back to my interview with Mr. Yoshida. Indeed, Beuys employed many craft materials such as felt, fat in addition to wooden and metallic pieces borrowed from the nomadic traditions, but he did it in a way where he kept his position as the artist, the author of these works. But Mr. Yoshida, after being questioned about the conceptual reasoning of why he used to produce white painting in 1977, gave up producing more paintings as an artist, and submitted himself to the historical exploration of traditional clothes and rags. These two paths at first seem to be in the opposite direction. However, it appeared to me that Mr. Yoshida’s journey was situated on an imaginary extended trajectory of Beuys, if he had stayed alive longer.

Or maybe not. In the end, Beuys stayed a star figure in the art world where conceptual authorship is basically attributed to an individual. But Yoshida’s installation (which I haven’t seen physically, unfortunately), despite the fact he’s attributed as the author artist, embodies the collective history of the collected clothes, with all the stories of their anonymous makers and wearers in the past hundreds of years. This difference is radical and gives us an important clue for thinking seriously how to go beyond our current perception of the art world, and its relation with the traditional worlds of craft.

- License:

- CC-BY