“It’s my most important function. To be a teacher is my greatest work of art. The rest is the waste product, a demonstration. If you want to explain yourself you must present something tangible. But after a while this has only the function of a historic document. Objects aren’t very important for me anymore. I want to get to the origin of matter, to the thought behind it. Thought, speech, communication –– and not only in the socialist sense of the word –– are all expressions of the free human being.”

This is a quote by Joseph Beuys, as his answer to Willoughby Sharp’s question on teaching during an interview on Artforum in 1969[1]. Back then, he had already been teaching for about eight years at the Düsseldorf Academy of Fine Arts. Later in 1972, he was dismissed from his professorship. Beuys and Heinrich Böll issued a manifesto on the foundation of a ‘Free International School for Creativity and Interdisciplinary Research’ in the following year.

The Education programme of beuys on/off is directed by two Co-leading Associates, myself and Teayoon Choi. We are working with Programme Associate, Jaemin Shin in South Korea, in collaboration with three Guest Associates, Gulnara Kasmalieva and Muratbek Djumaliev in Kyrgyzstan and Aigerim Kapar in Kazakhstan. I am a researcher of contemporary art and media and I teach at universities in Japan. We are currently preparing a series of online seminars titled Summer School of Unlearning which will be held between July and September in 2021.

I invited Carl-Peter Buschkühle, the author of Joseph Beuys and the Artistic Education: Theory and Practice of an Artistic Art Education (Leiden: Brill, 2020) to write an article for our first posting, which provides historical and pedagogical contexts to our project. At an informal seminar held on January 21, Buschkühle shared his experience and research with the members of beuys on/off. Born in 1957, he belongs to the generation who had chances to visit Beuys’s studio and join ongoing discussion or come across Beuys on the street nearby the Academy. I was surprised to hear that Beuys was always around and available for the generation of artists and researchers near Düsseldorf. Buschkühle was also invited to Beuys’s house when he was preparing his doctoral dissertation “Warm-Time –– Art as Pedagogy in the Work of Joseph Beuys”. Sadly, this invitation was not realized since Beuys passed away by heart attack on January 23, 1986.

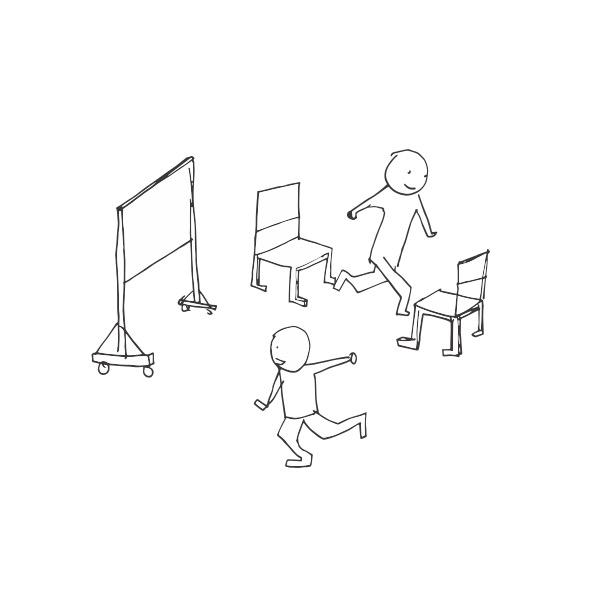

During the seminar, Buschkühle stressed Beuys’s basic concept about pedagogy; communication is a learning process. One who is speaking is a teacher and others listening to him/her are pupils. Spontaneously, another way round in the next. Buschkühle called this learning process ‘fluid communication.’ This could be understood as one of the important missions of Summer School of Unlearning. We define unlearning as ‘a way to resist the systemic oppression and violence formalized in bureaucracies of knowledge production’. Accordingly, if a learning process liberates participants from the hierarchy in academia and predetermined ideas about education, it is also an unlearning process.

The title of this introductory essay came from Gert Biesta’s book, Letting Art Teach: Art Education ‘After’ Joseph Beuys. Putting Beuys’s action ‘How to explain pictures to a dead hare’ (1965) as a staging of teaching, Biesta argues that art is ‘the ongoing challenge of figuring out what it might mean to be in dialogue with the world’, and ‘what it might mean to reconcile oneself to reality and to try to be at home in the world.[2]’ In this respect, our activities can be described as mutual teaching in art, bridging four different communities across Eurasia and East Asia, and sharing diverse educational practices.

Inspired by Beuys’s words, we start from our own reality of contemporary life for Summer School of Unlearning. “One can no longer start from the academic concept of educating great artists –– that is always a happy coincidence. What one can start from is the idea that art and experiences gained from art can form an element that flows back into life.[3]” We will critically interpret this idea to begin our unlearning.

[1] Sharp, W. (1969). Interview as quoted in Energy Plan for the Western man – Joseph Beuys in America, compiled by Carin Kuoni, New York: Four Walls Eight Windows, 1993, p. 85.

[2] Gert Biesta, Letting Art Teach: Art Education ‘After’ Joseph Beuys, Arnhem: ArtEZ Press, 2017, p.118

[3] Caroline Tisdall, Joseph Beuys, New York: The Solomon R. Guggenheim Museum, 1979, p.265

- License:

- CC-BY-NC-ND