The Importance of Pedagogy

Pedagogy plays a central role in Joseph Beuys’s artistic oeuvre. This is true to such an extent that any interpretation of his works, theory, and artistic practice remains necessarily incomplete unless it takes stock of the pedagogical dimension. Beuys’s commitment to pedagogy is evident in three interwoven aspects of his work, which cannot be separated into individual elements without falsifying the whole. The work directly relates to his theories on the expanded definition of art and the social sculpture, and vice versa. Beuys’s indefatigable engagement with artistic institutions should also be understood in this context. His professorship at the Art Academy of Düsseldorf should be seen as only one facet of a complex whole; his participation in discussions and events belongs just as much to his pedagogical activities as does his founding of institutions such as the German Student’s Party (GSP) or the Free International University (FIU).

The institutional aspects of Beuys’s pedagogical engagement flow out of his work’s educational ambitions. Through artistic and pedagogical engagement, Beuys intended to fundamentally ‘revolutionize’ contemporary paradigms through art. He developed this approach through a critique of materialism, the rationalism of contemporary culture, and its focus on economics. During Beuys’s lifetime, global political relations were largely dominated by the clash of two economic systems, capitalism and socialism. Despite their major differences, both shared a materialist-rationalist worldview. Politically, Beuys championed a unification of the positive elements of both systems: a free market and social commitments. He therefore supported a ‘third way,’ and was a founding member of the German Green party. But Beuys wanted more than to simply change economic and social systems—he wanted to change people’s ways of thinking. Thus, one of the central ambitions of Beuys’s art was to change paradigms of thought. His engagement took three main paths: his artworks; the theory of the expanded definition of art as ‘anthropological’ artwork (Harlan, Rappmann, Schata 1984, 20); and the ‘permanent conference’ of events and discussions (Beuys 1985, 6).

In many of his remarks, Beuys emphasizes the pedagogical character of his art, while the art, in turn, must be understood as a configuration of work, theory, and presence. “I require pedagogical conception, epistemological conception, and action itself.” (Harlan, Rappmann, Schata, 1984, 43). This statement enumerates three significant aspects of Beuys’s art. His pedagogical conception is closely tied to an epistemological one, and the confluence of both produces a call to action which moves far beyond traditional artistic practices within the atelier and gallery. Beuys was firmly convinced that art could be pedagogically effective in moving thought outside of the reductive framework of rationalism. He intended to do more than widen the epistemological and aesthetic purview of art to engage with the rationalist frameworks of science, technology, and economics, as has been done from Romanticism onwards. Beuys expanded the field of art pedagogy by, on the one hand, emphasizing its contemporary relevance via intellectual history, and on the other, projecting that it could prove healing for the future. When asked whether he believed in the therapeutic aspect of art, he replied: “Yes, it is the therapeutic process itself. I see no aspects. It is the most foundational thing about art.” (Harlan, Rappmann, Schata 1984, 21) Beuys believed that materialism was a development within intellectual history that urgently required therapy. He dramatized its effects in religious and mythological vocabulary: “Man must suffer the consequences of crucifixion, the full embodiment in the sensuous world through materialism. He must die, he must be completely abandoned by God, just as Christ was abandoned by the father in this mystery. Only when nothing is left will man discover Christ’s substance within his self-consciousness and perceive it fully. This is a realization. It is precise and must be undertaken precisely, like an experiment in a laboratory.” (Mennekes 1989, 22)

The Crisis of Intellectual History and the Discovery of Creative Consciousness

This statement, which Beuys delivered during a conversation with the Jesuit priest Friedhelm Mennekes, points to several important aspects of Beuys’s historical diagnosis, epistemological critique, and anthropology of the creative human. The worldview Beuys alludes to within the Christian context of suffering and resurrection is connected to his conception of the intellectual development of Western thought as portrayed in his drawing Evolution. The drawing charts the development of Western thought from its early rationalist beginnings in Greek philosophy (Plato, Aristotle) into the present, which is characterized by a materialist ideology in which religious and metaphysical ideas have been completely devalued. The path toward the vanishing-point of metaphysics leads through the development of critical scientific thought within the natural and the human sciences. Beuys considers the disappearance of metaphysics a loss, but by no means advocates for a return to bygone belief systems or mystical practices. Quite the opposite: in the second part of his statement, he explicitly calls for precise knowledge, knowledge of self as exact as the results of a laboratory experiment.

Art must deliver the self-knowledge Beuys calls for within a materialist world, which could, in Beuys’s lifetime, be roughly described by keywords such as capitalism, socialism, science, and technology. Shamanist practices in his actions are not anachronistic rituals but can become sources of self-knowledge within contemporary action art. Actions such as The Chief or How to Explain Pictures to a Dead Hare can be understood within the context of a conceptually-grounded theory of artistic thought. Just like the results of a laboratory experiment, these actions, as well as Beuys’s drawings and objects, only become comprehensible through a sustained exploration of the material. Such an engagement opens up paths of reflection which interact with Beuys’s artistic theory and horizons of meaning, but also stimulate critical and self-critical reflection. This perceptual foundation forms the aesthetic basis of Beuys’s exploration of consciousness and self-consciousness within his artworks. While this nexus is crucial for the reception of Beuys’s art, it also reveals a central characteristic of Beuys’s art pedagogy. The works are neither formal aesthetic pieces, nor embodiments or symbols of mythological, idealistic, or idiosyncratic ideas. Rather, they try to train the observer in the process of perception. They are pedagogical, even therapeutic objects or actions, and attempt to produce an experience of self-consciousness through the interaction with art.

“The outward appearance of every object I make is equivalent to an aspect of inner human life.” (Tisdall 1979, 70) When one surrenders to the works, one can discover important aspects of inner human life—specifically, aspects of spiritual life and thought. In his discussion with Mennekes, Beuys refers to this as “Christ’s substance.” This phrase naturally caused this peculiar statement to be interpreted as mythical speculation—aside from the religious context of the interview, of course. However, in the context of intellectual, religious, philosophical, and art history, this term references a long tradition of emancipatory thought. In a printed postcard from 1971, Beuys captions a Neapolitan image of the Sacred Heart of Jesus with “The Inventor of the Steam Engine.” He thereby underscores that Christianity, by emphasizing the development of the individual, also underlies the traditions of Enlightenment, science, and technology until the present.

“Christ’s substance,” which self-consciousness is supposed to discover and liberate, is creativity. Beuys’s famous statement, “Everyone is an artist,” (Harlan, Rappmann, Schata 1984, 102) means precisely this: every human is a creative being. This creativity can manifest in many different ways. It can reveal itself in painting, music, or literature, but it can also be evident in politics, engineering, medicine, or manual skills. Art in the narrower sense—the act of visual creation and the discussion of perception, feelings, concepts, and ideas—can therefore become a foundational education for everyone, a general course of studies not designed merely to widen the horizons of a coterie of specialists, but to promote a foundation of creativity as a form of existential potential (Harlan, Rappmann, Schata 1984, 39). This context explains Beuys’s decision to accept every student who wanted to study with him at the Düsseldorf Art Academy without an obligatory entrance exam.

Creativity as Capital in the Art of Living

The pedagogical goal of Beuys’s art is therefore to foster creativity. He embeds ‘creativity’ in catchy formulations which point to the full scope of its meaning. The expanded definition of art, which should be understood as an existential definition of art, is also contained within these formulations. Beuys invokes a historical philosophical term which was already used in Greek antiquity: that of Lebenskunst, or the art of living, which emphasizes each individual’s creativity and responsibility in developing him- or herself to take part in society. It is no coincidence that term has become popular again within contemporary philosophy since the late 1990s (see Schmid 1998). The art of living, which does only apply to bohemian dandies or aesthetes, is a demanding—even precarious—challenge leveled at each person, particularly in times of crisis, in which long-held traditions, values, worldviews, and social and economic structures are no longer reliable or effective. Beuys considered his era a time of crisis, as he describes in his 1978 ‘Appeal for an Alternative’ (Harlan, Rappmann, Schata 1984, 129–136), and by pointing to the ‘experience of Golgotha’ undergone by everyone (see Mennekes 1989, 22). When one is abandoned by God, thrown back on oneself, and all old beliefs are dead, nihilism ensues.

Beuys’s nihilistic diagnosis of his materialist era remains unaware of the further developments neoliberalism would undergo, from a multinational, supercharged capitalism to the ubiquitous simulacra spread by mass media. In particular, he could not anticipate the effects of social media networks, which were first celebrated as platforms that could facilitate democratic discourse and organization (for example, during the Arab Spring) and have now become a major threat to democratic social orders. This essay was written only two weeks after Trump’s frenzied supporters stormed the Capitol in Washington, DC. We might consider Beuys’s idealistic belief in the power of creativity to help democracy thrive a failure in the face of political machinations, smear campaigns, and conspiracy theories worming their way through the Internet. Presumably, he would have greeted the interactive potential of digital communication as a formidable medium for holding a ‘permanent conference.’ He once made a statement in this vein on using satellite television to broadcast global activities of the FIU (Harlan, Rappmann, Schata 1984, 40). However, despite these statements, we should not forget that Beuys believed the key to fruitful social progress lay in the individual development of creativity.

“The only revolutionary power is creativity. The only revolutionary power is art.” “Creativity = social wealth = capital.” (Harlan, Rappmann, Schata 1984, 59, 60). In these catchy, slogan-like statements, Beuys connected creativity to art, politics, education, and economics. Beuys uses the word in its original Latin sense of ‘creare’—to produce, bring forth—to describe the capacities of creative thought and action. But he does not leave it at this general definition. Rather, his art represents ongoing research into the nature and development of creativity. In the quotations above, creativity must be understood in a wide variety of senses. It is not only derived from individual talent or practice; it is also a social good, representing national wealth and capital that is developed through the creative capacities of ‘artists of life’ who are engaged in the creation of a ‘social sculpture.’ This should not occur within the strictures of an existing sociopolitical system, but rather be ‘revolutionary’ by expanding thought itself.

Beuys’s artistic pedagogy cannot be separated from its revolutionary intentions and intended results. His artworks are a key pedagogical tool to this end. The fact that they still provoke confusion, excitement, shock, and amusement in today’s audiences is quite in line with Beuys’s strategy. However, these reactions are not the primary goal of the artworks; rather, they are byproducts of their conceptual and material makeup. The fact that they do not please or mollify but instead provoke their viewers belongs to their ‘revolutionary’ pedagogical goal. Beuys said that he wants to make “something cook” in the viewer (Beuys 1979). Art students should “be properly kneaded through from one end to the other.” (Beuys 1969, 53) This is a rather different approach to traditional art lessons, which emphasize visual analysis and the study of techniques. In an interview conducted with Siegfried Neuenhausen in the trade journal Kunst + Unterricht, Beuys explicitly rejects traditional art instruction. He speaks of an “isolated helplessness within the damn concept of the artistic” (Beuys 1969, 52). Concretely, he discusses the example of a “little nose” drawn by a student. Student drawings are often quite schematic. But even in simple situations, artistic confrontation can take place. “When someone has made a clichéd drawing, it’s good to say: ‘Look at the nice little nose you’ve drawn. I’ll show you an anatomical atlas in which you can look up what kind of nose you’ve drawn…’ One can’t allow the student to simply make something artistic. One must think in larger contexts.” (Beuys 1969, 52, 53). The drawing of the nose becomes an opportunity to “confront the student with something new within him.” (Ibid.) For the art teacher, Beuys is a “catalyst” for intensified and expanded processes of experience, understanding, and creation. These kinds of artistic practices are evidently interdisciplinary. Through research and reflection, the thoughtless schematic form of a nose can produce new realizations about anatomy and nature, which in turn can inspire and refine artistic practice. Experience and reflection interact. Since creative work requires students to infuse their personal interests and thoughts into the demands of the work, interdisciplinary learning, in which they must make creative connections themselves, demands that they activate various mental processes and fully engage with the material. Here, artistic learning is reconfigured as a complex process, in comparison to prevailing operationalized learning processes, which measure success through tests and assessments.

The full name of the FIU, the “Free International University for Creativity and Interdisciplinary Research,” belies the complexity of this form of artistic pedagogy. It references two decisive factors necessary for artistic education: training creativity by developing an individual’s own capacities; and thinking in large, interdisciplinary contexts. Creative thought processes open and transform relevant fields depending on the themes, questions, or objects discussed. Beuys speaks of developing a “presence of mind” through artistic pedagogy by connecting complex thought processes to broader contextual understanding (Harlan 1988, 60). The production of meaning and perspective through presence of mind can be understood as an existential “narrative” that is produced by each individual as an ‘artist’ or ‘artist of living’ (Schmid 1998, 255).

The Expansion of Artistic Thought

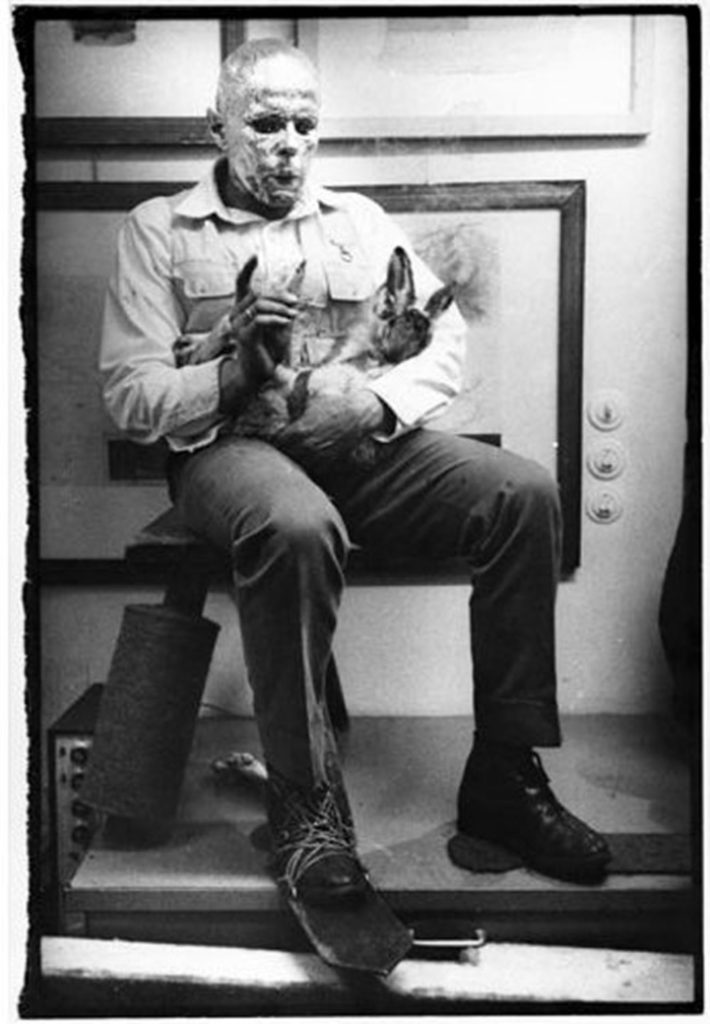

Traditional educational settings are generally characterized by a rationalist approach to disciplinary material. Art’s ‘revolutionizing’ of thought seeks to break this dominant approach. However, this does not mean that Beuys calls for irrationality in the learning process—at least not as a sweeping countermeasure. As he states during his Manresa action, “I am searching for Element 3.” Element 3 is a mode of thought that does not culminate in contrasts such as rational versus irrational, but rather connects the two and puts them into a dynamic relationship with one another. Beuys subjects the irrational to nuanced investigation. This manifests visibly in his artworks, since viewing and interpreting them requires both rationality and intuition. Beuys characterizes artistic thought as a mixture of both. The mixture of gold and honey, which Beuys smears on his head in the action How to Explain Pictures to a Dead Hare, symbolizes the dynamic relationship of these two poles. The action, in which Beuys conducts a meditative conversation with the hare cradled in his arms, also demonstrates a careful attention towards the encounter, which, as this essay will show, is also an important element of his art and pedagogy.

While the concept of rationality has been thoroughly examined in psychology and epistemology, intuition has received less systematic analysis or attention. Beuys’s works open up spaces for intuition, but he also engages with the theory behind it. As in other aspects of his work—including his ideas for a future society in which law, economics, and the human sciences interact like a ‘three-limbed organism,’—Beuys draws upon Rudolf Steiner in his psychology of creative thought. Steiner characterizes intuition as the ‘totality’ of a cognitive process which manifests in a confluence of will, feeling, and thought. This occurs, for example, in an “immersion” within phenomena, which Steiner understands as an expression of the “power of love in spiritual form.” (Steiner 1987, 142, 143) Such an ‘immersion’ is an important aspect of Beuys’s artworks, which resist an easy or quick reception and require slow, engaged, and complex engagement.

The melding of intuition and rationality in artistic thought is not only a hallmark of Beuys’s own pedagogy, but also of a Beuys-inspired ‘artistic education’ developed into a separate pedagogical method (Buschkühle 1997, 2997, 2017, 2020). The theory and practice of this artistic education further distinguishes between the various characteristics of artistic thought, which Steiner and Beuys allude to in their holistic understandings of intuition. The two describe the three components of human mental activity as will, feeling, and thought. In this context, thought largely refers to rational thought, which Kant, for example, ascribed to the faculties of reason and understanding. (Kant 1977, 109, 311) Feeling is also a significant factor that contributes to the effect, experience, and understanding of artworks.

However, rational thought, feeling, and intuition do not adequately account for the full complexity of creative and artistic thought. One essential factor of creativity is imagination. With this, I do not mean the reproductive power of imagination, which allows us to recall ideas of things, events, or people that are not present. Productive imagination allows us to imagine something that has never existed before. This can occur intuitively in the creation of an artwork, in which the current state of the work inspires the next steps. Such productive capacities of the imagination are often vague at first and require an exertion of willpower to achieve realization. At the same time, working on a new concept stimulates reflection on knowledge, experience, and personal intentions, as well as new attention to the new forms and colors in a painting, for example, and an understanding of the effects they produce. Thus will, feeling, reflection, and imagination make up the ‘totality’ of artistic thought. Added to this are skills which bridge mental activity and material production, and which are tied to bodily organs and instruments

In contrast to the ‘totality’ of intuition emphasized by Steiner and Beuys, this differentiated understanding of mental operations can deliver more precise insights for pedagogy. The totality of intuition can be understood and experienced as “momentary multiplicity” (Buschkühle 2017, 228), in which multiplicity is produced through the interaction of cognition, feeling, imagination, and knowledge or experience. Each individual element may transform and develop intuition as a whole. Deepened knowledge and experience, a more fully developed sense of perception and feeling, or a developed imagination can all transform intuition. The power of the will also affects the quality of artistic intuition.

Artistic education should therefore have the pedagogical goal of developing complex artistic thought, understood as an interaction of sensitive perception, independent imagination, critical reflection, willpower, and skills (Buschkühle 2020, 53). Artistic education inspired by Beuys’s pedagogical model seeks to foster these capacities. It can develop creativity: an existential creativity understood against the horizon of an expanded, anthropological conception of art. In this context, specific artistic accomplishments in school art classes are merely spaces for practicing existential creativity. The old phrase, “We do not learn for school, but for life,” is reconfigured against a new horizon.

The Sculptural Warmth of Artistic Communication

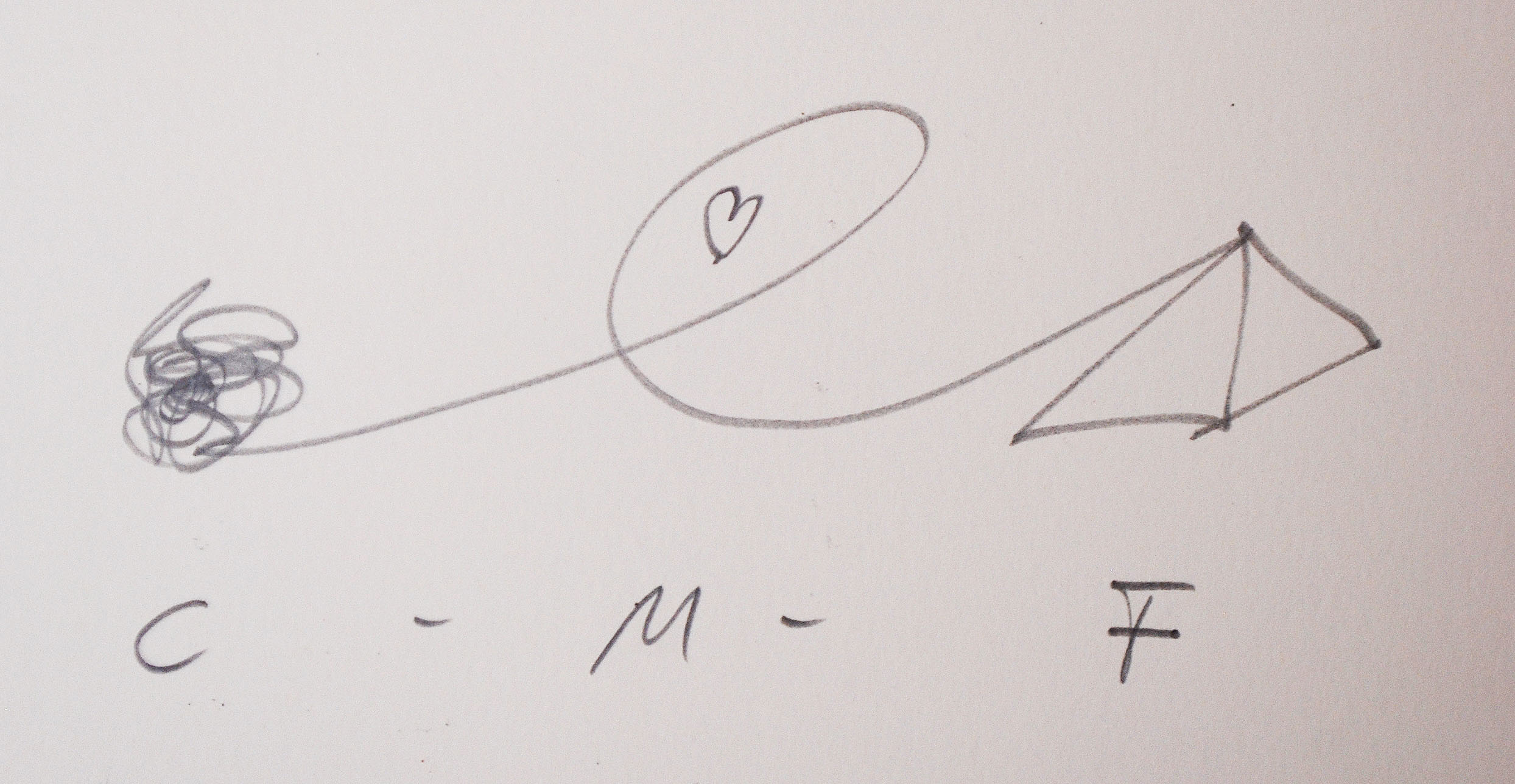

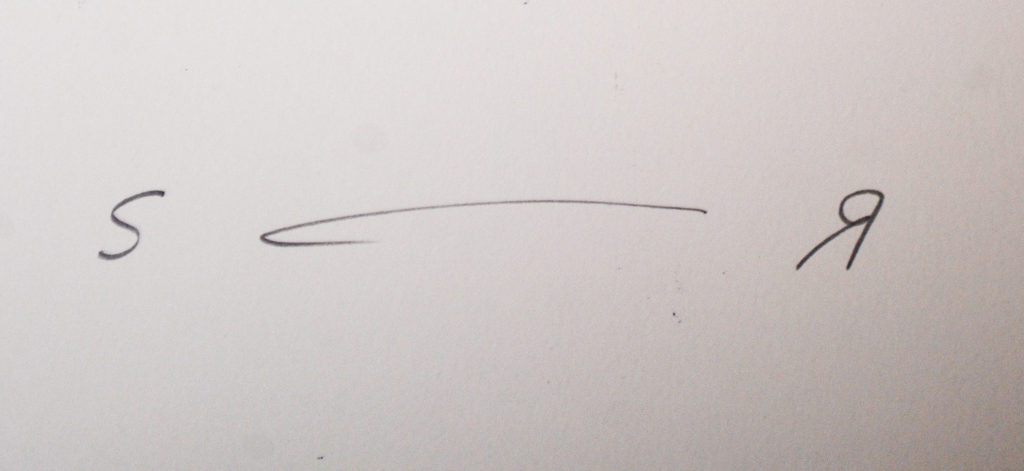

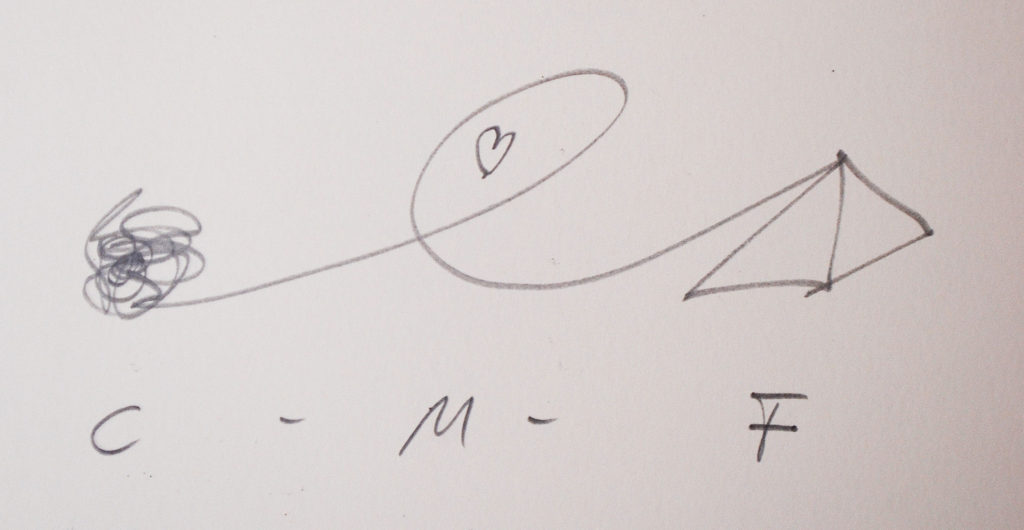

In his thought, Beuys employs core terms of communication theory, such as the ‘sender-receiver model.’ In Beuys’s diagrams, the letter ‘R’ for receiver is turned towards the ‘S’ of the sender, and thus is given an active role. The curved form of the Eurasia Staff, whose crook points back towards the artist, also indicates the active reflection required by the receiver to perceive signals from the sender.

Artists, for example, can become attentive, active receivers by paying attention to their encounter with a material, an emergent form, or a content. This is not a hegemonic form of communication in which the interests of the initiating party dictate the terms of engagement. Hegemonic communication patterns occur in situations where one party attempts to exploit the other, whether in the human relationship with the natural world, in which natural resources are extracted and refined into products, or in human relationships, in which employees are treated as ‘human capital.’ In contrast to these forms of ‘hierarchical’ communication, artistic communication is more of a “non-hierarchical discourse.” (Habermas 1981) While Habermas, however, largely charts out non-hierarchical discourse within the rational plane of understanding and reason, artistic discourse goes further in using intuitive as well as rational thought in engaging with the other, and activates emotion, empathy, and imagination. A dialogue of this sort requires a good will and thus contains an ethical dimension. This good will is described by Beuys, who is inspired by Steiner’s anthropology and psychology, as an internal “warming process.” The warm quality of artistic communication is a term that cannot only be grasped through reason, but requires intuitive insight into the required internal state and attitude. Yet it remains a concept that Beuys insists everyone recognize in their precise experience of their individual “Christ substance.” Beuys articulates the social dimensions of this concept as follows: “Where alienation now separates humans—in a cold sculpture, so to speak—a warm sculpture must come to exist. Warmth towards others must be generated. This is love. This is at the root of the mysterious concept of Christ.” (Harlan, Rappmann, Schata 1984, 21)

This attentive, mimetic, constructive, and reflective act of communication is highly important for artistic education. It connects inner and outer creativity, artistic thought and action in the world. Processes of artistic education practice a ‘culture of inquiry’—rather than a culture of hierarchy or subjugation—in which the artist takes responsibility by ‘listening’ to something and attempting to do it justice. A culture of inquiry can be practiced in the reception of artworks, media images, natural objects, and social practices, as well as in the production of artworks, in which students express their own opinions on a given topic. The direction of an individual work process mobilizes creative thought and action, since the goal is not to gain knowledge that can be tested in an exam, but instead to produce personal representations as a reflection on cultural and social topics (see Buschkühle 2007, 2017, 2020).

Sculptural Movements of Artistic Education

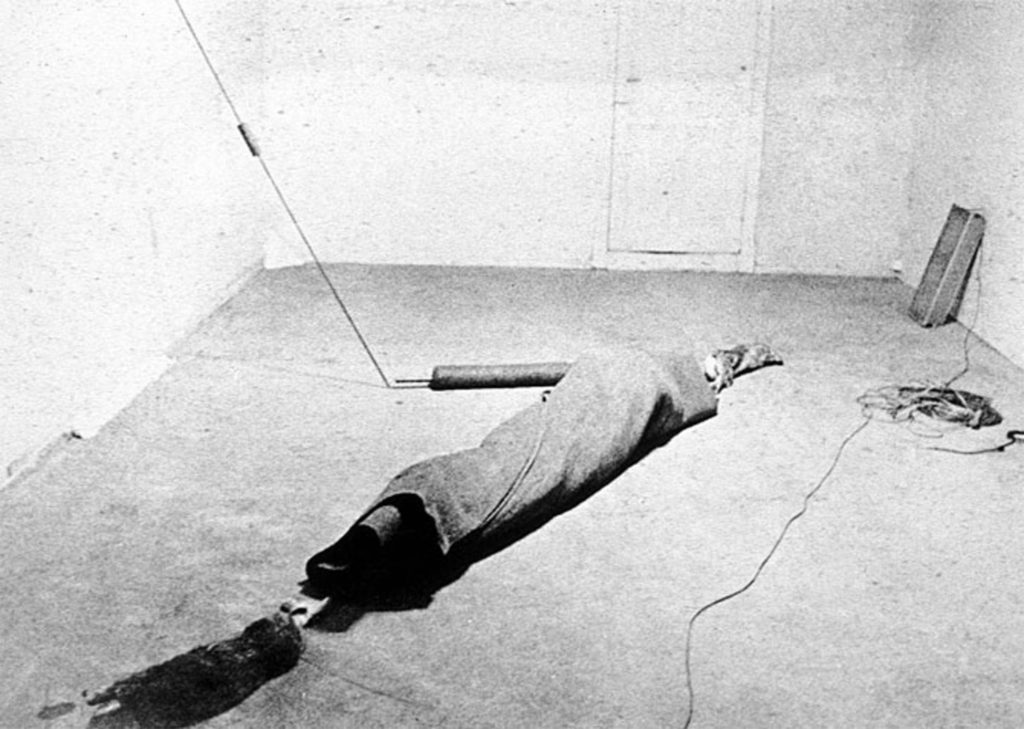

Far from indulging in mythical ruminations, Beuys’s art has the pedagogical goal of liberating a free, creative ethics. Since this ethics must be self-reliant and constantly reinvent itself anew, Beuys describes this process in his sculptural theory through the triad of chaos, movement, and form. When artistic production takes place in the narrow sense, as in the creation of a painting, it manifests a continued rhythm of formation. The work is formed between phases of chaos, in which it is unclear how to begin or continue, and phases of creative activity, which either culminate in a finished form or a renewed state of chaos if the work is ‘not yet satisfied with itself’ (an insight which is largely intuitive, but also rational). All creative processes which attempt to produce something new can be understood using this model, including the process of building an ethical or moral judgment. The destabilizing force of chaos mobilizes all other available forces to find solutions and create forms. This creative process is not a frivolous form of play in which ‘fantasy is given free reign.’ In a questioning culture, it is a precarious, even distressing process, in which one must fight for success. Beuys believes that distress is a great creative motor. He specifically highlighted this in his action The Chief, in which he staged a state of artistic reception by lying between two dead hares for eight hours wrapped in a roll of felt (Buschkühle 2020, 30). In the serious, self-reflective mode, which this action brings to the viewer and submits to empathetic perception and reflection, the gravity of the artistic approach is demonstrated. It clearly requires a strengthened and active will to endure. It also initiates a dialogue between author and viewer, which does not occur on the level of connoisseurship, but in the empathetic production of inner distress, suffering, and empathy that can start an internal ‘revolution’: “Indeed such an action changes me radically … Theme: How does one become a revolutionary? That’s the problem.” (Tisdall 1979, 95)

The movement between chaos and form is crucial for artistic processes. It requires a different approach from lesson sequences, in which facts or knowledge are imparted step by step, and evaluated using exams. Traditional lessons are largely designed to exclude uncertainty, chaos, or unanticipated dynamics. Creative processes in theme-oriented artistic projects, by contrast, must by default involve a dynamic exchange between chaos and form in order to spark the skills and responsibility of the participants. Critique is therefore a driving force of the creative process, and central to a culture of inquiry. It mobilizes various elements of artistic thought and sparks the creative process, as well as research and reflection on relevant (and perhaps interdisciplinary) knowledge. Everything can be questioned in the creative process. In the social sculpture of the ‘permanent conference,’ productive, well-meant critique occurs between four poles: the work, topic, student, and teacher are engaged in a continual exchange, and communicate their demands, responses, reactions, and answers. Mistakes cannot occur in a creative process, unlike operationalized teaching units. Any mistakes are approached through a culture of inquiry, a ‘loving’ and caring attitude, while suffering asserts itself as a motivational force when the student is confronted with a preliminary sense of failure. “The mistakes made in a first attempt may reveal themselves to be unexpected blessings,” Beuys declared (Harlan 1988, 37). The mistakes may catalyze a phase of chaos, but this is precisely the work’s way of expressing that it is not yet finished, or the content’s way of asserting that one has not dealt with it properly, or showing the student that he or she has not yet learned enough and requires “confrontation with the new” (Beuys 1969, 53). Recognizing mistakes requires sensitive perception and critical reflection to reconfigure them as an opportunity for improving one’s work, willpower, and the ability to imagine the next steps in the work.

Critique produces a creative exchange between the various elements of artistic thought. The ‘totality’ of this thought should not be understood as a form of ‘psychic harmony.’ Sensitive perception can critique the foundations of reason; imagination can provoke rational or emotional engagements; feeling, reason, or both can critique a lack of willpower. Creative achievements, new insights, ideas, and actions result from the conflict between these mental faculties. The process always occurs between the poles of chaos and form, crisis and resolution. This endless, precarious rhythm sometimes generates a certain amount of distress, and produces a longing for quick solutions borne out of habits, directives, orders, worldviews, religious systems, or conspiracy theories. Yet the dynamic rhythm produced by the critical exchange of various mental faculties is a force of personal freedom, as well as social democratic freedom. Promoting this critical process through artistic education is therefore also a commitment towards individual and social freedom and responsibility. In this context, this project also ties into Beuys’s statement “Everyone is an artist,” which is inspired by a humanist Enlightenment tradition, and carries emancipatory political consequences for creating the social sculpture.

The Practice of Artistic Education

Inspired by Beuys’s artistic pedagogy, a theory of artistic education has developed in Germanophone countries since the 1990s. Artistic education attempts to integrate central aspects of Beuys’s artistic pedagogy within school teaching and extracurricular art classes. An artistic project is thus conceived as an artistic form of education. Traditional art classes usually focus on the interpretation of artworks or media images, and the practical application of techniques or aesthetic concepts. They emphasize analysis and use. However, rather than developing individual creativity, such an approach usually reinforces a student’s ability to conform to the frameworks suggested by existent artworks or the teacher. Instead of establishing a pedagogical method that facilitates freedom, this approach instead fosters obedience. It therefore produces the opposite of what Beuys hoped for in artistic pedagogy.

Understanding an artistic project as a form of artistic education creates different affordances and possibilities. Traditional art lessons generally favor a deductive approach, in which students analyze an artwork, and then—if all goes well, and students are able to work independently—replicate the properties of the analyzed work elsewhere. By contrast, an artistic project proceeds inductively. It begins with a period of research, in which knowledge is gathered about the topic at hand. This research delivers necessary criteria for the artistic work. The gathered information provides students with a means of orientation and a set of challenges for engaging with the topic. This process is an integral part of experimental artistic work, in which the dynamic movement of creativity which Beuys characterized as ‘chaos – movement – form’ plays a central role. Students are challenged to make artworks that express their own positions towards a theme. Each student finds his or her own approach to the topic. This fosters their own responsibility and ‘warmth of will.’ The creative process mobilizes all available faculties of creative thought: paying attention to what the emergent form is ‘saying,’ imagining possible creative developments, critically reflecting on form and content. Does the form express what I want it to say? Do I know enough about the topic to approach it properly? These perceptions, expectations, and reflections are stimulated by a culture of inquiry in which students learn to become ‘receivers’ of their work and focus on the expressive content of the ‘sender.’

The work process and content-oriented research are linked through a dynamic feedback process, which leads to the third structural hallmark of the artistic project: contextuality. Context is doubly important in an artistic project. Each student must undertake their own research on the demands of their work at every given moment—they must research the topic as well as the technical or manual skills required to solve particular artistic problems. In addition, context also refers to the connections between the project phases and the work process. John Dewey, who championed the project method as a primary means of stimulating independent thought, compared the contextuality of the project process, in which knowledge, experience, ideas, and expressive forms grow increasingly complex, with a river. Just as the river widens and deepens from source to estuary as tributaries join it, independent engagement with a topic will provoke intensified and broadened learning.

Each phase of the artistic project builds upon the previous one. For example, in a project that engages with the topic of ‘Freedom and Dignity’—including the philosophical dimensions of these terms—self-portraits of the students in their real environments or in imagined roles may take center stage. These self-portraits may give students the opportunity to reflect on personal freedom and questions of dignity. These are central terms of the first article of the Universal Declaration of Human Rights, which was discussed in class. A critical examination of political art and media images opened up other contexts by moving beyond individual issues to address existential, social, and political problems. This expanded perspective led to a second work phase in which students created posters to express their own research, reflections, and imaginative ideas about ‘Freedom and Dignity.’

The teacher has a complex role in artistic learning projects. He or she must be knowledgeable on the topic, comfortable working between disciplines if necessary, and must determine a framework for the project. It is challenging to find an inductive point of entry that can simultaneously introduce students to new content and stimulate individual creative reflection. By determining this point of entry, the teacher sets the course for the project’s further development, both in terms of its teaching content and the stimulation of individual creativity. Over the course of the project, the teacher accompanies the students in their work process, supporting them and ‘confronting them with the new,’ as Beuys put it, to stimulate the students to think and act in ‘larger contexts.’ This can occur through group lessons on the basic foundations of the topic and group exercises in techniques, but also through one-on-one conversations with students about their work. The teacher should also give each student individual tasks for research, reflection, and practice. It is all-important for the teacher to be an artist, so he or she can provide appropriate support for these artistic projects. He or she must have personally experienced the creative process, its necessary movement between chaos and form, the artist’s responsibility towards content and form, and its demands on artistic thought, in order to effectively support the students.

Educational processes within an artistic project take place between four central elements: work, content, student, and teacher. These processes are marked by induction, experimentation, and contextuality. Their elements can be separated into the research on relevant, often interdisciplinary knowledge fields, the construction of meaning, and the creation of connections and transformations through individual artistic representation. The themes of artistic projects can accordingly be as varied as human life itself. A theme could concern a physical material, such as paper. It could be a political or philosophical topic, such as ‘Freedom and Dignity.’ It could examine scientific or technical topics, such as ‘The Leaf Principle – Bionics,’ or critically examine cultural phenomena, such as ‘Kitsch as Art.’ Astonishing artistic projects, such as those by Mario Urlaß, can be led in primary schools, or they can take place in an extracurricular context and focus on topics such as trauma, as Christian Wagner has documented in artistic projects with students from disadvantaged schools.

We can illustrate the artistic project’s demands on a student’s capacities for artistic thought and action through student work produced in the ‘Kitsch as Art’ project. Students were asked to undermine a piece of kitsch by highlighting its kitschy attributes and critically transforming them through alterations and interventions. The work produced by a fifteen-year-old female student demonstrates artistic thought and processes in action. For her piece, the student used a Barbie doll from her own collection: she took this doll out of its usual context and transformed it to bring a critical eye to bear on the Barbie. She dressed the doll in new clothes of her own design, such as an asymmetric skirt made of leopard fur, and a metallic cape with a zig-zag edge. Sweeping black and pink ‘wings,’ which fan out like a peacock’s feathers, were attached to the doll’s back. Upon closer observation, one can see that the doll’s eyes have been changed: they are perfectly made-up and still have long lashes, but the pupils look like those of a crocodile. This transformation of the eyes is not completely novel, but it is a subtle way to permanently transform the doll’s ‘personality.’ The blue doe eyes become those of a predator.

Such a work is the product of varied reflection, and can only be made when all capacities of artistic and creative thought have been activated. The student perceptively noted that the Barbie, which is often blonde, represents an ideal of female beauty often embodied by models or actresses. Barbie is therefore always dressed fashionably, whether in a sporty dress or evening gown. The student’s research on the doll, which preceded her work on it, revealed that the doll’s proportions were unnatural and exaggerated: the limbs were too long, the waist too small, the face was neatly made up and yet child-like, with big eyes and a small mouth and nose. These proportions have been chosen to psychologically produce the impression of ‘cuteness,’ while the doll also functions as an ideal prototype for the body and fashion image of young girls.

The latter insight demands critical reflection on broader contexts, such as the world of media and fashion. The student’s research also suggested that the Barbie’s bodily and stylistic traits contained sexual aspects. The student therefore needed to exercise careful perception and critical reflection in order to tease out these aspects, a process which naturally had to be fostered in class. The teacher took on the role of a companion who stimulates the student to further reflections, questions, and supports the student through conversations.

This research formed the context for the student’s choice to transform the doll into an unabashed vamp. Her modest clothing was transformed into a cabaret costume, her child-like face into a made-up canvas with an animal element. Imagination is required to transform this figure piece by piece and element by element. The imagination is clearly also informed by clichés. But precisely by consciously adapting these elements to a new context, the clichéd clothing, body, and gestures were transformed into elements that critically interact with one another. In order to realize this vision, certain skills were required, such as sewing or neatly painting the pupils.

Interdisciplinary reflection takes place during the research and brainstorming phase. In the case of the Barbie, the student engaged with cultural aspects of fashion and media, the sociocultural perception of women, and the psychological effects of facial expressions, gestures, body shape, and clothing. She built up a narrative by putting these diverse areas into relation with one another. This allowed the student to put together an existential narrative, which is made up of diverse relevant aspects, and required for creating meaning and action. An existential narrative can be produced by an inquisitive process of artistic learning, and is developed by gaining familiarity with the topic, as well as through critical and self-critical reflection. Ideas that arise and inspire continued work on the piece are subject to critical consideration, with respect to their content and effects. Critique thus becomes a driving force of creativity. It occasions chaos and stimulates the movement towards new form. Chaos is the force that ‘kneads’ students ‘through from one end to the other,’ and occasions ‘inner movement,’ as Beuys demanded of artistic learning that could ‘revolutionize’ thought. This requires a willingness to overcome the subjective and focus on the objective demands of the work and content. The artist must then continue to exert his or her efforts until perception, reflection, and imagination all agree ‘that the work is finished.’ (Buschkühle 2017, p. 178 ff) In this artistic process, the culture of inquiry becomes a foundation on which one can develop an ethos that orients itself towards particular circumstances and challenges, and derives its judgments and actions from particular conditions. This stance promotes a creative ethics that can be practiced in processes of artistic reflection. However, beyond this narrow pedagogical context, it points to the art of living practiced by a free subject, which can independently, and of its own volition, exert its creativity in the creation of the ‘social sculpture.’

Bibliography

- Beuys, Joseph: Das Bildnerische ist unmoralisch. Gespräch mit Siegfried Neuenhausen. In: Kunst + Unterricht 4/1969, 50 – 53

- Beuys, Joseph: Spuren in Italien, Kunstmuseum Lucerne 1979

- Beuys, Joseph: Ein kurzes erstes Bild von dem konkreten Wirkungsfelde der Sozialen Kunst, Wangen 1985

- Buschkühle, Carl-Peter: Wärmezeit. Zur Kunst als Kunstpädagogik von Joseph Beuys. Frankfurt am Main 1997

- Buschkühle, Carl-Peter: Joseph Beuys and the Artistic Education. Theory and Practice of an Artistic Art Education, Leiden, Boston 2020

- Habermas, Jürgen: Theorie des kommunikativen Handelns, Frankfurt am Main 1981

- Harlan,Volker, Rappmann, Rainer, Schata, Peter: Soziale Plastik. Materialien zu Joseph Beuys [1976], ³1984

- Harlan, Volker: Was ist Kunst? Werkstattgespräch mit Beuys, [1986], ³1988

- Kant, Immanuel: Kritik der reinen Vernunft [1781], Frankfurt am Main ³1977

- Mennekes, Friedhelm: Beuys zu Christus. Beuys on Christ. Eine Position im Gespräch, Stuttgart 1989

- Schmid, Wilhelm: Philosophie der Lebenskunst. Eine Grundlegung, Frankfurt am Main 1998

- Steiner, Rudolf: Philosophie der Freiheit [1893], Dornach 1987

- Caroline Tisdall (Ed.): Joseph Beuys, Salomon R. Guggenheim Museum, New York 1979

- Urlaß, Mario: Art Class as a Construction Site. In: Buschkühle 2020, 200 – 216

- Wagner, Christian: On the Educational Potential of Art: A Requiem for Schönau. In: Buschkühle 2020, 217 – 231

Figures

- How to Explain Pictures to a Dead Hare © 2008 Artists Rights Society (ARS), New York / VG Bild-Kunst, Bonn

- Beuys’ diagram of artistic communication (Carl-Peter Buschkühle)

- Chaos – Movement – Form. Beuys’ diagram of the plastic process of creativity (Carl-Peter Buschkühle)

- The Chief, 1964. © 2008 Artists Rights Society (ARS), New York / VG Bild-Kunst, Bonn

- Barbie as a Vamp. Student’s work. (© Carl-Peter Buschkühle)

- License:

- Other License