Trash Festival: Beginnings

Joseph Beuys began 7,000 Oaks at documenta 7 in Kassel, Germany, in 1982 and took five years to complete it. Beuys assumed that these trees would be planted all the way to Russia. Nine years after he started, the Soviet Union collapsed and many things changed, and now the people of the post-Soviet republics live under a completely different paradigm.

For us, as students of the ArtEast School for Contemporary Art, this work by Beuys became an important statement: art can raise political problems and engage people in saving the already fragile environmental balance. It is also a bright example of the struggle against authority and capital’s destruction of nature in their desire for profit. Twelve years ago, we were inspired by this work of Beuys and together decided to initiate the ecological festival Trash. At that time, we did not realize how this experience would change our lives not only through knowledge, but also by expanding our worldview and making us more sensitive to the essence of life. The first iteration of Trash (2009) responded to environmental pollution in Kyrgyzstan and was an attempt through art to attract the attention of people and power to these challenges. We chose Osh Bazaar – the dirtiest place at the time in Bishkek City – as a site emblematic of our ecological and social problems.

Each participant was a former student of the school and worked in their own way to question our society. Rasul Kochkorbaev and Anatoly Kolesnikov (our dear friend who has already passed away) opened a discussion about plastic and how in the Soviet Union people did not have this problem by using recycled packaging. Diana Ukhina made video, Separation, about the short life of our food and the decomposition process. It was also important to collaborate with local workers and audiences: Nikolai Cherkasov made a mobile wash-handing wagon for the women who sell snacks at the market; Maksat Bolotbekov brought brushes with paint and offered people the chance to colour the old bridge; Dmitry Petrovsky graffitied the concrete wall with images of little paper boats – a symbol of childhood – sailing down the Ala-Archa river and getting stuck due to mountains of garbage in the river; and Nellya Dzhamanbaeva worked with local authorities to clean up the river.

The bazaar is always a place for performic beggars, a place for communication. It was quite symbolic to make a kind of costume parade there with a big dragon made of plastic bottles and bags. Taking the dragon as a symbol of the river and with screaming slogans written on the handmade billboards, a noisy procession of young people attracted the attention of market workers and customers. Later, the festival ended with a noise performance by Aytegin Muratbek Uluu.

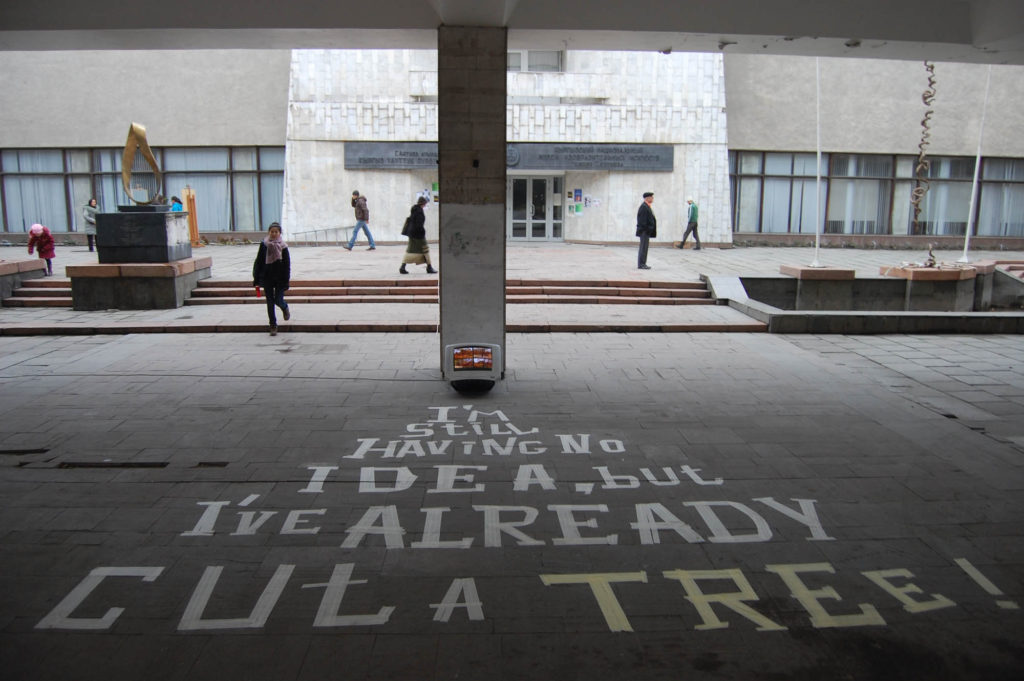

The second festival, TRASH-II: Make a forest, curated by Diana Ukhina and Bermet Borubaeva, was held in front of the National Museum of Fine Art in 2011. It is a central area with many passersby and thus a spontaneous audience. This event was not only about the global problem of deforestation but also problems within the city. Bishkek was one of the greenest cities in the Soviet era but is today losing its green zones due to privatization and road extensions. Artists dedicated their works to these ecological problems and presented them to attract public attention. This festival was only a one-day event but nevertheless made us think that we should keep going and continue doing work in this direction.

Restarting the Festival: TRASH III: Art and Ecology

After a ten-year break we decided to restart the festival based on a platform of the Bishkek School of Contemporary Art, created by the former students of ArtEast School. This platform opens new opportunities for rethinking art production processes by self-organizing artists in Central Asia.

This year we literally went to the trashiest place ever you can imagine – Bishkek’s municipal dump, which has not been re-cultivated during the last sixty years. Nowadays, the issue of environmental problems in cities is extremely relevant and Bishkek is no exception: a stinking landfill, smog, agricultural land polluted by production, hyper-motorization and many other problems in the city endanger the health and lives of its people. Bishkek almost permanently ranks worst in the world among large cities whose air quality causes illness and economic loss. Its roots lie in a tangle of problems: weak management; a low level of environmental awareness; bribery; overproduction of the neoliberal economic system, which exploits natural resources to extract maximum benefits with minimal means; and ignorance of environmental safety.

We chose Altyn-Kazyk, a district that lies between the city dump and the Ala-Archinsky water reservoir, as the location for the festival. It is surprisingly less than thirty minutes by car from the city centre but there is a world of difference between Bishkek and this new district that has appeared near the landfill. People live in conditions without clean water, cultural spaces, libraries or cinemas; in many ways, there is nothing here. The government has already received international support for a landfill reclamation project in the form of 22 million euros from the European Bank for Reconstruction and Development. The project should have been completed several years ago, but is still not finished yet, even though the budget is already spent. No one had any sense of responsibility about it and none of the politicians really care about developing the community and the common good of the people suffering from the landfill.

Problems of environmental inequality became the main agenda for the art festival’s research group. How to create a conscious dialogue among all participants about solving the issue of environmental pollution in the city? I was really inspired by the energy of everyone who put their efforts into the festival. Artists, activists, scientists, citizens and thinkers all contributed to this process of communication in different ways: by experimenting or analysing, through art interventions or by creating art events, objects or publications. They shared their research and methodologies on how we can deal with environmental challenges at the local and global levels.

There were people who had never participated in any art exhibition before and artists who were already internationally known. What united them was their passion and an infinite desire to express their concern about what is happening around them.

One of the most important things for us was opening a “library of saved books” that we built in our imaginations after our walks and talks with local residents. We rented a small shop and, together with Ravshan Ta Djing, created a local community centre for kids, where they can play, make art, read books, have lectures or take courses. This spot is now a window between two worlds, offering the opportunity to start dialogue and collective creativity.

The library is a community centre that plays a very important role in socialization and bringing together the two completely polar worlds of the city centre and the landfill neighborhood that had no chance to intersect before. With minimal decor for the space, furniture in the form of old chairs that were painted and fruit boxes for bookshelves, and the magic of art, this space became a favourite spot for residents, a place where they can feel a sense of belonging, try something new and gather together with others.

The first three months’ rent was supported by international donors but the question we now face is how we can sustain the space and prolong it independently. We hope we can organize further support to ensure this space continues to exist. It is also vital that local people are involved in the organization and in initiating their own agenda for the space. We next need to consider the fourth iteration of Trash as a festival that can present dialogue, assuming it is possible to hold the event in these turbulent times though which we are living.

In terms of the number of artists and other participants, the third edition of Trash produced a radical shift in our perception of reality and highlighted environmental injustice. We all felt like we were asphyxiating throughout the whole day we spent in Altyn-Kazyk, but the local people live there permanently. And this is frightening.

Through Trash, we can see that our efforts can change things. Art offers a space for the impossible and it gives hope when our ideas, memories and thoughts take shape. This is probably what we took away from this festival. Our existential experiences of touring around the landfill, then around the incredibly beautiful water reservoirs just nearby, and of observing how children live right next to the landfill and breathe in the toxic air – all of these experiences made us think about the footprints left behind by our civilization.

- License:

- CC-BY