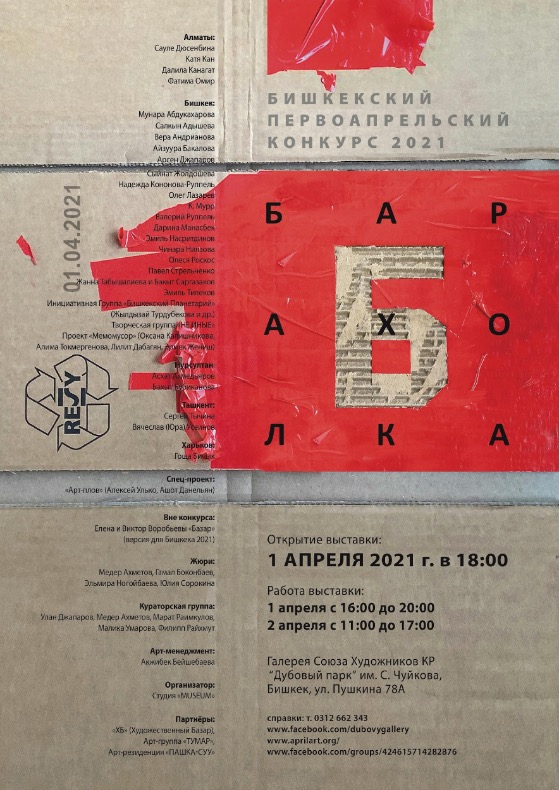

During our last interview Mizuki Takahashi asked us relevant questions: “In general, artists are people who create and produce. How can artists justify their practices when the excessive production of things is damaging nature and the environment? How can artists sustain their artistic practices without production?” Since our answer was perhaps not comprehensive enough, we would like to expand our response through several examples of artworks from the April First Exhibition, which opened in Bishkek, Kyrgyzstan, just a few days after the interview.

The exhibition, which is dedicated to April Fool’s Day, was originally the idea of the architect and curator Ulan Djaparov from Bishkek and is on-going since 2003. The low-budget event usually attracts many participants from the Central Asian contemporary art community because of its informal atmosphere, making it a good place to test out new artworks and meet friends. This time, the curatorial group including Ulan Djaparov, Malika Umarova, Marat Raymkulov, Meder Ahmetov and Philipp Reichmuth selected thirty applicants from Kazakhstan, Kyrgyzstan, Ukraine and Uzbekistan.

There are no restrictions on age, media and background for participants: the youngest one this time, Arsen Djaparov, was nine years old, while the oldest was a well-known artist, Valery Ruppel, who is seventy-two. Meder Akhmetov interpreted the format of the exhibition as “a kind of ontological anarchy, where you have age transgressions – children’s art and Grand Prix artist exhibited next to each other.” Ulan Djaparov usually compares this contest with the ancient Olympics sport of pankration, a fight without rules, only here the athletes are artists, all of whom have the chance to apply to participate. There are international juries every year and some symbolic prizes traditionally provided by Tumar Art Group. Every year curators propose a relevant theme and title.

Exhibition view. Center; Yelena and Victor Vorobyevs. Bazaar. Installation.

Photo by Aysalkyn Adysheva

This year’s title was “Flea Market” and was a continuation of the Art Bazaar online project initiated by artist Darina Manasbek, architect and artist Meder Ahmetov and anthropologist Philipp Reichmuth. As written on its Facebook page: “The Art Bazaar is a volunteer-run private Facebook group where Central Asian artists sell their work, and where artists, collectors, curators and art lovers can discover and comment on the works on display. For every three pieces that an artist sells, they buy one artwork from another Art Bazaar participant, thereby supporting each other. The Art Bazaar has been active since April 2020, when it was born as a mutual support project during the pandemic. Since then, it has been creating a unique new space for conversations around contemporary art in Central Asia.”

At the exhibition artists also have the opportunity to sell their artworks according to flea market rules, “where the process of exchange, reboot and renewal for some, and the acquisition of experience and immersion in a different context for others, takes place. The difference between the flea market and the bazaar is that the things (objects) almost always have their own history; they bear the imprint of time, the personality of the owner.”

Special Jury Prize.

Photo by Muratbek Djumaliev

The exhibition takes place for only two days and this year was held at Oak Park, the official gallery of the Union of Artists of the Kyrgyz Republic. Located in the historical centre of Bishek, the gallery attracted many visitors despite the growing number of Covid-19 infections. The audience is usually very excited about the next April First Exhibition because it always provides strong artistic interpretations of the social and political agendas in Central Asia.

One of the first works a visitor saw (and smelled) was an installation featuring elegantly designed packages and an ash-like residue on a cup. The smell was evocative of the Kyrgyz countryside with domestic animals and cooking on an open fire. The packages seemed like items ready for export, labelled as they were in English “Sheep Dung Cake” and proclaiming that they were “pressed and dried” and a “high-quality organic product from Kyrgyzstan”.

Smell of the Motherland is a sharp and ironic installation by Bishkek-based artist Emil Tilekov, making a subtle critique of growing nationalism with its sacralization of traditional attributes and of the very real stagnation of energy economics in Kyrgyzstan. Tilekov’s work reminds us of the words of former president Kurmanbek Bakiev, who was calling on people to heat houses with cow dung during the energy crisis in 2008. Indeed, traditionally cow or sheep dung was the oldest fuel of the nomads of Central Asia but is it what we really have to strive for?

Emil Tilekov. Smell of the Motherland. Installation.

Special Prize from Discussion Platform Esimde. Photo by Muratbek Djumaliev

I wanted to be an artist – but I sell sunflower seeds was an interactive installation by Gosia Biczyk, a Polish cultural anthropologist currently based in Ukraine. A pile of sunflower seeds on a traditional Central Asian low round table invited visitors to sit around, talk and chew. Made in the format of socially engaged art, it referenced the local grassroots tradition of chewing sunflower seeds. Having lived and worked in Central Asia for many years, Biczyk is familiar with the local context and has strong ties and friendships with many artists here. As she explained, her role in the Central Asian contemporary art community is rather as the sower of seeds than an artist.

Gosia Biczyk, I wanted to be an artist – but I sell sunflower seeds. Interactive installation.

Photo by Muratbek Djumaliev

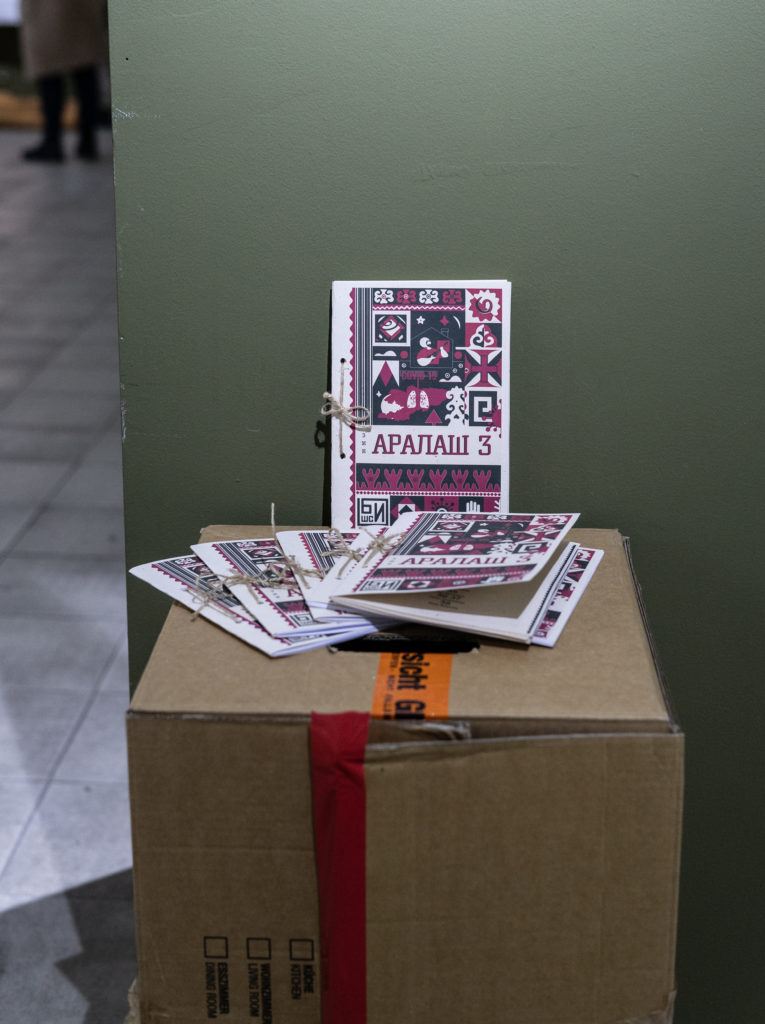

The flea market was also a place to buy publications. The zine Aralash-3, produced by Bishkek School of Contemporary Art, was quite popular among visitors. It featured various reflections on the Covid-19 lockdown last year. It was printed with a regular office printer on recycled paper and is also available online.

Photo by Muratbek Djumaliev

It is noteworthy that this platform already organized an open-air exhibition in an actual flea market in Bishkek on 20 December 2020. This exhibition was a reaction to the socio-political situation in Kyrgyzstan. For Bishkek School of Contemporary Art, “moving the exhibition space to the flea market is a symbolic gesture, reflecting the transfer of official politics to the current field of informal relations, which have no laws”.

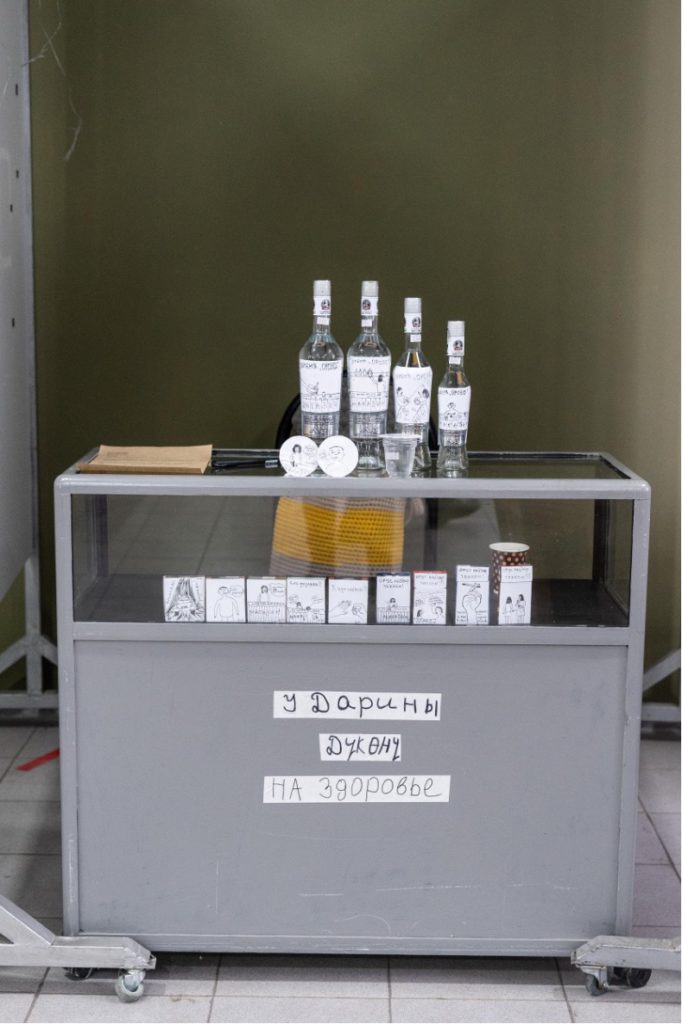

The Grand Prix winner this year was Darina Manasbek, an artist from Bishkek. Her work was an installation reproducing a small shop “where everyone could buy shots of vodka and cigarettes”. Instead of labels on the bottles, cigarettes and boxes of condoms, though, there were her personal stories written by hand. These stories were about her experience as a teenager working in her family’s tiny shop in the so-called Working-Class Town, a district in Bishkek built in the Soviet era for workers at the Lenin Factory, the biggest factory in Central Asia and which produced ammunition for Kalashnikovs.

This was one of the stories, which was written on a box of condom: “‘Got a rubber band?!’ A man came in and said this. I was so small and didn’t even understand what he meant. I said we didn’t have hair bands. And so, he was like, ‘Do you have condoms?’ and I told him that we don’t sell them! He got visibly upset, abruptly leaving and getting into his car. I went out after him and there was a woman in glasses waiting in his car, smoking a cigarette with the window open. He drove off. And I stood and watched the departing car. Our roads were basic and unpaved, and the car left behind a ball of dirt . . .”

Darina Manasbek. Shop. Installation. Photo by Aysalkyn Adysheva

Close to the exit of the gallery was Saule Dyussenbina, an artist from Almaty, Kazakhstan, who played the role of “bazarcom”, a local bazaar administrator who usually gives permissions and licenses to trade in the market. She actually wrote “certificates of authenticity” on specially designed paper for all the artworks sold at the exhibition. Everyone who bought something at the exhibition paid 200 som, or approximately 2 euros, to get the “official verification” for their purchased artwork. This smart performance that incorporated a critique of the institutional ecosystem behind the global art market won a special prize.

Saule Dyussenbina. Certificate of Authenticity or Parasites are Everywhere. Performance.

Photo by Ulan Djaparov

Our final example from the exhibition is an installation by K. Murr with a jar of tomatoes on a white chair, a photo of the jar of tomatoes and a text about nutrition. K. Murr is obviously an alias, a reference to the novel The Life and Opinions of the Tomcat Murr by E. T. A. Hoffmann and bearing a striking resemblance to R. Mutt, the pseudonym used by Marcel Duchamp for his Fountain in 1917. Jar of Tomatoes became a way to show the artist’s position about art objects, art institutions and sustainability.

K. Murr, Jar of Tomatoes. Installation. Photo by Askhat Akhmedyarov

The text read as follows:

What is an art object if not an implicit manifestation of conservation? The painter is priming a canvas, the sculptor covers bronze with a patina, the media artist is constantly concerned about data preservation on different hard drives. This activity is continued by the collector and museum curator, whose duty is to save the object from sunlight, humidity and mice. That’s why there are so many cats in the underground corridors of the State Hermitage Museum!

A good example of creativity is Piero Manzoni. He knew what to do – God bless his father, who owned a cannery! And today, to say “Campbell’s Soup Cans” is to make an overt reference to Andy Warhol. We still compete in a rat race to save art objects for centuries. Marcel Duchamp attempted to resist this without success. And from a marketing perspective, Joseph Kosuth’s One and Three Chairs conceptual installation is no more than firstly, a commodity itself, secondly, a photo advertisement and thirdly, a label.

Homemade conserves made during the Covid summer are free of the idea of “eternity” or “noteveryonewillbetakenintothefuture”. The date of expiry of the tomatoes is up to the owner and opening the jar of tomatoes and then eating them is a true artistic act!

K. Murr

- License:

- CC-BY